Saturday, 2 October 2021

Thoughtful Questioning: Why Cold Call Is Not Enough

Tuesday, 7 September 2021

Forensic Assessment

If you would like Aidan to work with you on developing pedagogy at your school, please visit his website at https://www.aidansevers.com/services and get in touch via the contact details that can be found there.

Saturday, 15 May 2021

Wednesday, 21 April 2021

From @HWRK_Magazine: What Should I Do If a Child Has Finished Their Work?

https://hwrkmagazine.co.uk/what-should-i-do-if-a-child-has-finished-their-work/

A common question, but countless potential solutions. I explore how to use time effectively when a student has finished their work earlier than anticipated.

You all recognise the scene: a line of children stretching from your desk to the classroom door and then doubling back on itself, snaking its way between desks and chairs, children waiting patiently (alright, not always patiently) to have their work seen and to receive their next instruction. To be honest, many of you will have solved the problem of the eternal queue, but the question remains:

What should I do if a child has finished their work?

Read on here: https://hwrkmagazine.co.uk/what-should-i-do-if-a-child-has-finished-their-work/

If you would like Aidan to work with you on developing pedagogy at your school, please visit his website at https://www.aidansevers.com/services and get in touch via the contact details that can be found there.

Monday, 28 December 2020

My Corona: A Christmas with Covid

There was a selfish fear too, of course: what if I come into

contact with someone who tests positive and have to isolate? Or what if one of

my own children gets sent home from their school?

My fears were, inevitably, pretty quickly realised: my

middle daughter came home on the penultimate Friday, destined to self-isolate

until Friday 18th. But that didn’t touch Christmas, but it meant a

huge burden on my wife, working at home fulfilling Christmas baking orders. I

hurried back from school every day in order to try to provide some relief.

Every day, that is, until Thursday.

Because, of course, it was the unthinkable that actually

happened.

Rewind to Wednesday night:

Wednesday night was a tough one: I had an inexplicable pain

across my lower back – I couldn’t get comfortable in bed and, along with the

accompanying nausea, it kept me awake most of the night.

I ‘woke up’ the next day feeling slightly unwell, in my own words. Thursday was to be the last day

in school, and not thinking that back ache and tiredness should stop me from

enjoying the last day of school, off I went.

Thankfully, I spent the day ensuring, as usual, that I was

social distancing, was in well-ventilated places, keeping my hands washed

regularly and so on. The day was a great way to end what had been a fantastic

term – yes, a challenging one, but a challenge I had relished. I was glad to

leave by the end though, as, due to a lack of sleep, or so I thought, I was

flagging somewhat.

At home I caught up a little with the DfE’s newly-revealed

plans to ask secondary schools to test pupils as of January. I fired off a

quick commiseration email to our principal (I work in an all-through academy)

and thought I’d forget about it. With one more work-from-home morning left to

go, I retired to bed that night, although not before a heated discussion with

my wife regarding whether or not I should get a Covid test: when my symptoms

are definitely those of Covid, was my stance; tomorrow, regardless, was hers –

so that we knew for certain whether or not our Christmas plans would be

affected.

But my subconscious brain clung on to the evening’s

thoughts, weaponising them and torturing me all night. I dreamt of having to

set up a testing centre at school – one of those looped dreams consisting of

bright colours (the testing booths were decorated with red and white Christmas

string), repeated phrases and nothing at all very tangible other than the

feeling of dread. I woke at 4:10 am and headed downstairs to book myself a

Covid test, the fever being such that the virus was becoming a more certain

possibility.

***

Just before lunchtime on Sunday the test result came back.

I’d all but convinced myself it would be negative, mainly on account of an

easing temperature and the presence of phlegm: it was a chest infection, it must

be.

Dear Aidan Severs

Your coronavirus test

result is positive. It means you had the virus when the test was done.

I went downstairs to break the news. By now, of course, the

rules for Christmas had changed, all our plans involved people now marooned in

tier 4, so my corona was not going to be the cause of spoiled Christmas plans.

However, there were plenty of other consequences.

I have to admit I cried. Many times. Everything set me off.

The thought of potentially ruining so many other Christmases. The fact my wife

had to cancel and refund all her Christmas orders. Knowing my mother-in-law,

who is in our bubble, would not be able to spend Christmas with us meaning that

she may face it alone. The knowledge that my children, who have soldiered on

through the country’s toughest restrictions, living as we do in Bradford, and

not even an area of Bradford that got out of local lockdown for a while, would

have to endure more time indoors with only each other as company. Heightened

emotions may be a symptom – then again, its legitimate for it to be that

upsetting without that as an excuse.

I completed my Test and Trace information, and the academy’s

counterpart. Thankfully it was deemed unnecessary to ask anyone else to

isolate, due to the mitigations in place and my keeping to them. That was a

weight off my mind, although I spent each day of the holiday waiting to hear

that someone else from work had come down with it because of me. At the time of

writing, I have heard only of one very tentative transmission, and am hoping

that when I speak to my colleagues again in the new year, all will report a

healthy Christmas holiday.

And the thing just left me weak, wheezy and a waste of

space. Unable to go out, incapable of doing anything of any value. I

par-watched a film, and an episode of a series. Reading, writing, music had

very little draw – besides the initial headache that came with my Covid

prohibited these activities. I slept on and off. I mostly just felt guilty – I

know it wasn’t my fault - and sad that my wife was having to take on

everything. My muscles ached, my skin felt like it was on fire, my head felt

like it was sunburnt.

At some point, it robbed me of my sense of smell, leaving me

with only a partial sense of taste. All that Christmas food! Would I be able to

taste it? That was if I even had the appetite for it – usually ravenous the

whole time, I certainly experienced some fluctuation in my desire to eat.

It felt unfair. We’d stuck to all the rules. I’d survived

the term, always being there at work, covering when others thought they might

have had it, or indeed, when others did have it, plugging away finding

never-ending solutions to all the latest Covid problems. We’d ridden wave after

wave of the UK’s harshest restrictions, very rarely losing hope.

Even after a week, I was still dog tired. I woke up on the

23rd feeling a bit brighter, a little more energised, but as the day

wore on, that wore off. If there’s one thing this virus does well, it’s robbing

its host of their vitality. Perhaps the exhaustion was due to my body fighting

of the illness effectively enough for me to remain at home, instead of being

hospitalised? I suppose if that was the case, then I am thankful for the

tiredness.

Of course, friends and family rallied round. Many a kind

message was received, people picked stuff up for us, dropped it off.

Entertainment for me and the children was sent. My wife did a cracking job of

keeping the morale high despite everything.

Christmas Eve was merry – I was feeling a lot better and

managed to join in with all the day’s activities – still inside the house,

isolating of course. Just before we headed out for a drive around to look at

the Christmas lights loads of my family members came to the street and sang to

us – a lovely, heart-warming moment, and a chance to sample some of my dad’s

Covid Carols live! But we weren’t only going to see the Christmas lights, we

also made a second trip to the test centre: my wife had begun with a cough

- a cough which by now was plaguing me

to the point of perceived pain in my lungs.

And on Christmas morning, whilst preparing the meal, her

text came through: positive.

And the so the saga continues. Thankfully by Sunday 27th

(my official release date) I was feeling normal enough again to do a decent job

of having a good time with the children, feeding the family and keeping the

house in some sort of semblance of order. I took the kids out for a brief walk

in the woods and it did us good. At the time of posting, my wife is still ill

in bed, experiencing her version of all the symptoms I had.

Wednesday, 23 December 2020

From @HWRK_Magazine: Staring At Snowflakes (Real Behaviour Management)

Having a bit of a laugh with students can actually be a great behaviour management technique in and of itself.

Wednesday, 11 November 2020

What The Headlines Didn't Tell You About Ofsted's Latest Covid-19 Report

Here’s what, if you haven’t read the full report, you

probably don’t yet know: some children have been more exposed to domestic

violence, there has been a rise in self-harm and some children have become more

involved in crime. But those are just some of the most concerning, negative

outcomes of the pandemic for some young people.

Here’s what else you might not know, according to Ofsted:

the vast majority of children have settled back into school, are being taught a

broad curriculum and leaders and teachers are doing an excellent job of

adapting necessarily with positive results.

But that sort of stuff does not a headline make, does it?

Wellbeing

When it comes to wellbeing of pupils, the report is clear:

‘leaders said that their pupils were generally happy to be back, and had

settled in well.’

The report also records that ‘leaders in most schools

continued to report that pupils were happy to be back. Pupils were described as

confident, resilient, calm and eager to learn. There was a general sense that

they appreciate school and each other more. Many leaders noticed that behaviour

has generally improved… Many emphasised that fewer pupils were needing

additional support than had been anticipated.’

Imagine the headlines we could have had: Pupils return to school with confidence and

resilience! Children eager to learn as they get back to school! Students defy

expectations in calm return to education!

In addition, Ofsted identify that schools are going above

and beyond in their response to ensure that pupils are happy and able to deal

with the changes the pandemic has brought: ‘Many schools of all types reported

a greater focus than usual on their personal, social and health education

(PSHE) curriculum to develop aspects such as resilience and independence and to

reinforce or improve learning behaviours, but also to address pupils’

anxieties. Some schools were also strengthening their PE provision to support

pupils’ physical and mental well-being.’

And it’s not only children who have got back to school and

got on with doing a great job, it’s the staff too, according to the report: ‘Leaders

said that their staff have generally adapted well to various changes, and are

working hard to make these work. They attributed this to frequent and effective

communication with staff as well as to a stronger sense of team spirit that has

emerged over the last few months.’

Further potential headlines for your delectation: School staff working hard to adapt to

changes! Strong sense of team spirit seen in schools!

And perhaps being at home hasn’t been such a bad thing for

children anyway; perhaps it isn’t just the fact that they are finally back at

school which has made for such positive changes: ‘Many leaders spoke positively

about pupils with SEND returning to school. In a couple of schools, leaders

noted that additional time spent at home had been positive for pupils with

SEND, who had returned with confidence.’

Attendance

One of the fears of school leaders in the summer was most

certainly around what attendance would look like come September. Fears have

been allayed, according to Ofsted’s report: ‘Around three quarters of the

schools visited reported having attendance that was similar to, or higher than,

this time last year… where attendance had improved, leaders often attributed this

to the work that they had done to build families’ trust during the first

national lockdown, and their continued efforts to inform and reassure parents

about the arrangements they had made to keep pupils safe in school.’

More headlines: Home-school

relationships improve: attendance rises! 2020 Attendance higher than ever!

And Ofsted even acknowledge just how thoughtful and flexible

school leaders are being in their commitment to children: ‘Leaders described

how they were working closely with parents and offering flexible arrangements

if these were needed to help pupils to return as soon as possible.’

Curriculum and Remote Learning

Much was said during lockdown regarding ‘gaps’ that would

appear in learning. I’m sure many school leaders considered whether or not to

slim down their curriculum, providing what might amount to an insubstantial

education which did not develop the whole child.

However, what Ofsted have seen is that leaders are ambitious

to return their schools to their usual full curriculum as soon as possible,

that most of the secondary schools were teaching all their usual subjects and

that many of the primary schools they visited were teaching all subjects.

Another favourite subject of lockdown discussion and thought

was remote learning. Public figures weighed in with their ideas, as did

parents, teachers and students. Would schools be able to truly provide remote

education to a suitable standard?

Well, Ofsted have found that ‘almost all schools were either

providing remote learning to pupils who were self-isolating or said that they

were ready to do so if needed’ and that most schools ‘were monitoring pupils’

access to the work provided or attendance at the remote lesson.’

They also report that leaders are responding well to their

findings, particularly that ‘during the first national lockdown, pupils reacted

very positively when there was live contact from teachers, so want to build on

that when needed.’

And again, leaders are adapting well to the new

circumstances, thinking outside of the box and ensuring that staff wellbeing is

a priority: ‘Leaders in a few schools explained how they were trying to

mitigate the additional demands on staff of providing remote learning, for

example through the help of teaching assistants, or having staff who took a

particular role in leading or modelling remote education.’

A further possible headline: Schools found to be providing full curriculum and good remote learning!

CPD

Remember how teachers were all lazy during lockdown and

should have been back at work? Well, turns out, they were actually working

really hard (surprise, surprise), not only providing aforementioned remote

learning but also taking the opportunity to sharpen their skills en masse: ‘staff

in many schools seized the opportunity for training and development during the

months when most pupils were not physically in school.’

Now that certainly won’t make the headlines: Teachers work hard despite perception of

journalists!

Learning ‘Loss’

And finally to the big one: have children fallen behind? Are

their gaps in their learning? Academically, has Covid-19 set children behind

where they should be?

Well, much is said in the report regarding this, however a

key takeaway should certainly be the following:

‘In the mainstream schools visited, there was no real

consensus about the extent of pupils’ learning loss as a result of the

disruption to their education.’

Correct headline: No

consensus on Covid learning loss!

This is where the main criticism of the report might come:

it is written in such a way that the negative is the focus.

For example, the report makes it clear that ‘some leaders commented that writing was also an issue for some pupils, including writing at length, spelling, grammar,

presentation, punctuation and handwriting.’ And it is this that then hits the

headlines, with the ‘some’ removed, of course. Such a statement becomes

‘Children forget how to write during lockdown’ when it is headlinified.

Indeed, the inverse statement surely is equally as true: ‘Most leaders commented that writing wasn’t an issue for most pupils, including

writing at length, spelling, grammar, presentation, punctuation and

handwriting’ or even ‘Most leaders

didn’t comment on writing being an issue for most children.’

Yes, it is right for schools to identify the negative impact

of the pandemic so as to make progress with children who have been affected,

but at the same time the positive impacts and the huge amount of work that has

already been done in this vein should surely be celebrated more widely.

Not just for the benefit of hardworking school staff either – as a parent I want to be reassured by both Ofsted and the media that schools are doing a great job with my children. Thankfully, I don’t have to rely on them to form my opinion: I know for certain my children’s school is doing a fantastic job, and I know the school I work in is too.

Tuesday, 8 September 2020

Questions To Guide Teacher Reflection

Tuesday, 25 August 2020

Finding Your True Teacher Persona

This blog post is now available at:

This blog post is now available at:

https://www.aidansevers.com/post/finding-your-true-teacher-persona

If you would like Aidan to work with you on developing teachers at your school, please visit his website at https://www.aidansevers.com/services and get in touch via the contact details that can be found there.

Friday, 19 June 2020

Back to School: Recovery or Catch Up?

We’ve been hearing a lot of talk about recovery with regards to the curriculum we teach when schools can eventually reopen to all children.

But the question must be asked, what are we trying to recover?

Are we trying to re-cover past material to ensure that it is secure? Are we trying to recover normality and perhaps just try to ignore this blip? Are we trying to help staff and children to recover mentally from the upheaval - similar to how a hospital patient might need to recover? Are we talking of something akin to roadside recovery where we fix a problem and send them on their way, give them a tow to get them to a destination or just give them a jump start?

Maybe we need to attempt to do all of these and more.

But the recent talk of ‘catch up’ does not help us to do any of the above.

When we normally think of catch up we think of small groups of children taking part in an intensive burst of input over a short amount of time - indeed, research shows that this is exactly how catch up interventions should be run so that they have maximum impact.

Can this be replicated for whole classes of children, some of whom will have been doing very little at home, others of whom may have followed all the home learning set and really prospered from that? We certainly need, as ever, an individualised, responsive approach for each child, but it is fairly certain that when we are all back in school we will be ‘behind’ where we normally would be, even if it means everyone is equally behind.

It would be foolish to think that by the end of the first term we will have caught up and will be able to continue as we were back in February and March. To believe this surely puts us on very shaky ground. Any kind of intensive approach to recovery is almost certain to negative repercussions, not least where children’s well-being is concerned - and that of staff, for that matter.

Year after year we hear stories from teachers escaping toxic schools and even leaving the profession who speak out on the hothousing, cramming, cheating, off-rolling, flattening the grass, and other morally bankrupt practices that go on in schools in the name of ‘getting good results’.

Well, back to my question: what are we trying to recover? How do we define ‘good results’? What result are we wanting from that first term back? That second term back? That third term?

How long are we willing to give this? We don’t know how long this will impact learning for - we’ve never had a period this long without children learning in classrooms. Perhaps it will barely leave a mark academically, perhaps the effects of it will be with us for years? Maybe we are overstating the potential impact on mental health and once we are back everyone will just be happy to be there, but maybe it will effect some of us for a good while yet.

What’s for sure, at least in my mind, is that we need a slow, blended approach to recovery. We must focus on the academic but we must not neglect everything else - bear in mind that phrase ‘the whole child’ and extend that to ‘the whole person’ so that it takes in all the people who will be working in schools when we can finally open properly to all.

We can not revert back to a system cowed by accountability - arranged around statutory assessment. Maybe they will scrap SATS this year, or edit the content that children will be tested on. Then again, maybe they won’t. Either way, schools - leaders and teachers - need to be brave enough to stand up for what is right for their children.

Ideally, we’d have an education department who, instead of telling us that modelling and feedback are the ideal way to teach, were willing to consult the profession in order to create a system-wide interim framework. A slimmed-down curriculum outlining the essentials and cutting some of the extraneous stuff from the Maths and English curriculum. Many schools are doing this piece of work so it would make sense if we were all singing off the same hymn sheet. If this was provided by the DfE then any statutory tests could be adapted accordingly - but this is the bluest of blue sky thinking.

And in suggesting that we limit the core subject curricula, I am certainly not suggesting that the whole curriculum is narrowed. Children will need the depth and breadth more than ever. We mustn’t let all the gained ground in terms of the wider curriculum be lost. We need the arts - I surely don’t even need to remind of the mental health benefits of partaking in creative endeavours. History and Geography learning is equally as valid (especially as they are the most interesting and captivating parts of the curriculum - fact): these must not fall victim to a curriculum narrowing which focuses solely on getting to children to ‘where they should’ be in Maths and English.

Who is to say, in 2020/2021, Post-Covid19, where a child ‘should be’? Perhaps we need to define this, or perhaps it’s not something we can even put our finger on.

I’m sure that if Lord Adonis read this I’d run the risk of becoming another of his apologists for failure, but that’s not what I am. What I am is an optimistic realist who wants the best for the children returning to our schools and the staff teaching them. What I am is someone who has observed the UK education system over a number of years and have seen schools who really run the risk of falling for rhetoric and accountability that leads to practice which does not best serve their key stakeholders. What I am is someone who is committed to getting all children back to school, back to work even, as quickly as is safely possible. I am a leader who is committed to the highest of standards but who won’t take shortcuts to get there.

When it comes to success(ful recovery) there are no shortcuts.

Some important other reads:

http://daisi.education/learning-loss/ - Learning Loss from Daisi Education (Data, Analysis & Insight for School Improvement)

https://www.adoptionuk.org/blog/the-myth-of-catching-up-after-covid-19 - The myth of ‘catching up’ after Covid-19 by Rebecca Brooks of Adoption UK

https://researchschool.org.uk/unity/news/canaries-down-the-coalmine-what-next-for-pupil-premium-strategy/ - Canaries Down the Coalmine: What Next for Pupil Premium Strategy? by Marc Rowland - Unity Pupil Premium Adviser

Friday, 15 May 2020

From @TeachPrimary Magazine: Sounds Like A Plan

Read my latest article for Teach Primary Magazine for free online, pages 50 and 51:

https://aplimages.s3.amazonaws.com/_tp/2020/0515-NewIssue/TP-14.4.pdf?utm_source=TPNewsletter&utm_medium=20200515&utm_campaign=Issue11

"Imagine a way of working that was not only more responsive to children’s needs, but was also better for teacher wellbeing. If there was such a way, surely we’d all want to be doing it? I’d like to suggest it is possible; that by planning learning sequences and designing lessons flexibly we can provide for individual needs without it being a huge burden on our time and energy.

In order to ensure that our planning and teaching doesn’t impact negatively on our wellbeing, we have to find an efficient way to work. And in order for something to be efficient, it usually needs to be simple. However, teaching can often be overcomplicated by myriad solutions for how to engage children, manage behaviour, include technology, make links to other subjects, and so on."

Monday, 10 February 2020

Thursday, 12 December 2019

Beware The Reverse-Engineered Curriculum (or The Potential Pitfalls Of Going For Retrieval Practice Pell-Mell)

Tuesday, 22 October 2019

In Praise Of The Written Lesson Evaluation (And The Motivating Power Of Success)

What I do remember, and resent, was the lesson evaluations that we were supposed to write. Inevitably, after a day full of teaching and an evening full of planning (repeat ad nauseam), they were never filled in whilst the lesson was fresh in my mind.

Well, 13 or so years after finishing my degree I've finally discovered that written evaluations actually can be quite useful.

The other day, after working with a group who had been selected as ones who would potentially struggle with a research and present task, I resorted to writing down some thoughts after a somewhat difficult time with them. Here's exactly what I wrote in my notebook that lunchtime:

Not a Torture, But a Joy (principle of the Kodaly Concept)

Today was not a joy. It was torture for all involved. 'Pulling teeth' was the phrase used by the head who overheard me 'teaching'. I was tortured by the lack of interest and engagement, as were the children (who were tortured by my frustration).

The task - research and present - has been dragging on for a few weeks now. Every session I scaffold the time and activity even more to try to combat the inactivity. But there is no drive, no determination, no will to research and present. It's not, I think, that the ancient civilisation of the Indus Valley means nothing to them, but that reading books, locating information and then preparing to re-present that information does not interest them.

I'm also fairly sure that the children in my group, selected for this very reason, don't know how to carry out such a process. This lack of skill has led to past experiences where they have felt unsuccessful in such a task - I assume. And this lack of feeling of success, I reason, must have led to the lack of desire to make an effort today.

I talk so often of 'lack'. I see that they need to experience success. Must some success be my main goal, then? By what means? What must I jettison in order to gain this success? Must we put something aside, at least for now, in order to gain what they currently lack: success, motivation, confidence.

A tentative yes - I must prioritise their experience of success over what I am currently trying to get out of them. And what is that? The skill of reading for a purpose: gaining knowledge. The skill of writing coherent sentences, paragraphs, texts in order for them to then present it verbally.

What will I give, then? How will I ensure that what I give provides them with something from which they can derive the experience of success, without attributing all the success to me and my provision?

What if I asked them what they wanted? Would that reveal what they are truly motivated to do?

Beyond this particular piece of work, how can learning become a joy rather than a torture for these children?

Next session:

- group discussion: ides for the presentation

- finish off revision of text - teacher-led/modelled

- edit text - shared work

- back to organisation of presentation - what needs to be done? Assign roles

- children prepare presentation; teacher to provide assistance where needed

Wednesday, 2 October 2019

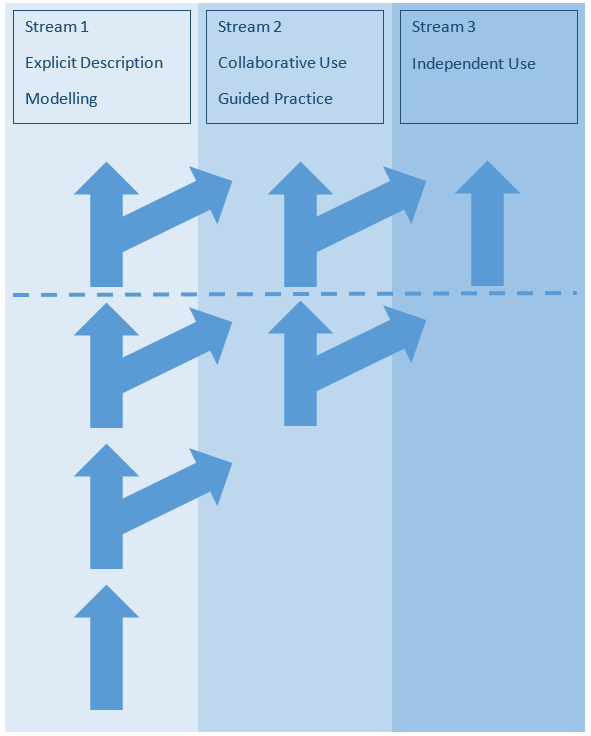

Responsiveness and the Release of Responsibility (A Model)

This article is now available at my website:

Monday, 16 September 2019

From the @TES Blog: 8 Routines For Teachers To Nail Before Half-Term

The Right Book for the Right Child (Guest Blog Post By Victoria Williamson)

It was the summer between fifth and sixth year of high school, when I was seventeen. I’d picked up Pride and Prejudice for the first time, but not because I actually wanted to read it. It was a stormy day despite it being July – too wet to walk up to the local library. It was back in the nineties before the internet, Kindle, and instant downloads were available. I wanted to curl up on the sofa to read, but I’d already been through every single book in the house. All that was left unread at the bottom of the bookshelf was a row of slightly faded classics belonging to my mother. I only picked the first one up as there was clearly a book-drought emergency going on, and I was desperate.

The reason I didn’t want to read it, was because I already knew it was going to be totally boring.

Well, I thought I knew it. I’d already ‘read’ the classics you see. When I was ten or eleven, thinking I was very clever, I branched out from my usual diet of fantasy and adventure books, and opened a copy of Bleak House by Charles Dickens. I can’t remember why now – it might have been another rainy day and another book emergency situation, but whatever the reason, I spent several miserable hours ploughing through page after page of unintelligible drivel about Lincoln’s Inn, Chancery, and a bunch of boring characters who said very dull things, before giving up in disgust.

I ‘knew’ from that point on that the classic novels teachers and book critics raved about were the literary equivalent of All Bran instead of Sugar Puffs, and I wasn’t interested in sampling any more.

I didn’t pick up another classic until that rainy day at seventeen, when I sped through Pride and Prejudice in a day and a night, emerging sleepy-eyed but breathless the next day to snatch Emma from the shelf before retreating back to my room to devour it. That summer, after running out of books by Austen, the Brontes and Mrs Gaskell, I tried Bleak House again. And what a difference! Where before I had waded thorough unintelligible passages without gaining any sense of what was going on, I now found an engaging, and often humorous tale of a tangled court system far beyond the ‘red tape’ that everyone was always complaining about in present-day newspapers. Where before I’d only seen dull characters who rambled on forever without saying anything at all, I discovered wit and caricature, and a cast of people I could empathise with.

That was when I realised that there wasn’t anything wrong with the literary classics – it was me who was the problem. Or rather, the mismatch between my reading ability when I was ten, and the understanding I had of the world at that age. I could read all of the words on the page, I just didn’t understand what half of them meant, and I thought the problem was with the story itself.

I was reminded of this little episode in my own reading history recently when I spent the summer in Zambia volunteering with the reading charity The Book Bus. One afternoon we were reading one-to-one with children in a community library, when I met Samuel. Samuel had a reading level far above the other children, and raced through the picture books and short stories they were struggling with. I asked him to pick a more complicated book to read with me for the last ten minutes, and after searching through the two bookshelves that comprised the small one-roomed library, he came back with a Ladybird book published in 1960, called ‘What to Look for in Autumn.’

He did his best with it. He could read all of the words – the descriptions of wood pigeons picking up the seeds to ‘fill their crops’, the harvesters – reapers, cutters and binders – putting the oats into ‘stooks’ and the information about various ‘mushrooms and fungi’, but he didn’t understand anything he was reading. Needless to say I looked out a more appropriate chapter book from the Book Bus’s well-stocked shelves for him to read the following week, but the incident reminded me of the importance of getting relevant books into children’s hands if we’re to ensure they’re not turned off by the reading experience.

This is a problem often encountered in schools when teachers are looking for books to recommend to children. A lot of the time we’re so focused on getting them to read ‘good’ books, the ones we enjoyed as children, or the ones deemed ‘worthy’ by critics, that we forget that reading ability isn’t the only thing we have to take into consideration. We have to match the child’s level of understanding to the texts that we’re recommending – or in the case of that Ladybird book, get rid of outdated books from our libraries entirely!

Children often find making the leap to more challenging books difficult, and comfort read the same books over and over again – sometimes even memorising them in anticipation of being asked to read aloud with an adult. If we’re to help them bridge this gap, we must make sure our recommendations are not only appropriate for their reading level, but match their understanding too, introducing new words and ideas gradually in ways that won’t put them off.

Samuel and I were both lucky – we loved reading enough that one bad experience wasn’t enough to put us off, but other children might not be so fortunate. Let’s ensure all children have the chance to discover the joy of reading, by getting the right books into the hands of the right child.

Samuel and I were both lucky – we loved reading enough that one bad experience wasn’t enough to put us off, but other children might not be so fortunate. Let’s ensure all children have the chance to discover the joy of reading, by getting the right books into the hands of the right child.Victoria Williamson is the author of Fox Girl and the White Gazelle (click here for my review) and The Boy with the Butterfly Mind, both published by Floris Books.

Thursday, 12 September 2019

Friday, 2 August 2019

Misguided Reading (6 Questions To Ask When Planning A Reading 'Lesson')

How should we teach reading? What do we even mean by 'reading'? Decoding? Comprehension? Both? Is it more than that?

|

| Scarborough's Reading Rope - image from EEF's 'Improving Literacy In KS2' |

If the above 8 headings (background knowledge; vocabulary; language structures etc) were all the necessary components of being able to read, is it the case that if we teach them all, children would be able to read? If so, how explicitly do they need to be taught? Can some of them be developed unwittingly in a language-rich, book-rich environment? Do teachers and schools really have a chance if a child isn't being brought up in such an environment?

So many questions, and given the range of advice that exists about reading instruction, I'm not sure we have the answers - at least not readily. Indeed, the 'reading wars' have been raging for years (although they focus less on comprehension) - just how exactly should we teach children to be able to read so that they can read words and understand their meaning as a whole?

My personal experience is that this is something that depends heavily on context. During my own career I have taught classes of children who have needed very little reading instruction and vice versa - I am judging this simply on their ability to understand what they have read. A cursory analysis of the differences between these classes reveals that it appears to me to be the children who have been brought up in a language-rich, book-rich environment who, by the time they are 10 or 11, can read exceptionally well and don't need teaching how to comprehend what they have read. Of course, some children will have been brought up in such an environment and still need help with their reading.

Why does context matter? Well, for the purposes of this blog post, it matters because what one teacher in one classroom in one school somewhere does, might not work for another teacher somewhere else.

For example, a reading lesson consisting of asking children to complete two pages of mixed written comprehension questions might work with children who can already decode, comprehend and encode, but it is questionable as to how much they will have actually learned during that lesson. A lesson like this might have the appearance of being successful in one setting but, share those resources online with a teacher in a different context and they might not experience the same levels of apparent success. The children in the second teacher's class might need teaching some strategies before they can access such an activity.

And what does said activity amount to in reality? Just another test. Weighing the pig won't make it fatter - it's just that weighing it also won't make it any lighter either: if a child can read already, then these kinds of activity might do no harm. But we must be clear: this practice of repeatedly giving children comprehension activities composed of mixed question types is not really teaching children much. However, perhaps the stress, or boredom, of constantly being weighed might start to have negative consequences for the pig: children are potentially put off reading if their main experience of it is repetitive comprehension activities.

So, if weighing the pig doesn't make it fatter, what does? Feeding it. But with what should we feed them with? What should we teach them in order to help them to read words and understand what they mean as a whole?

Is it as simple as Michael Rosen suggests? Is it just a case of sharing books with children and talking about them? I've seen first-hand anecdotal evidence which certainly suggests that 'Children are made readers on the laps of their parents' (Emilie Buchwald). My own children, taught very well to decode using phonics at school, also appear to be excellent comprehenders - they have grown up around family members who read an awful lot, have had models of high quality speech, have partaken in a wide variety of experiences, have broad vocabularies and spend a good deal of their own time reading or being read to. Give them a two-page comprehension activity and they'd probably ace it. However, as already mentioned, this certainly won't be the case for every child brought up in such a way.

But what should schools do when they receive children who haven't had the privilege of a language-rich, book-rich and knowledge-rich upbringing, or those for whom that hasn't quite led to them being excellent readers? Downloading someone else's comprehension sheets and making children spend half an hour doing them isn't going to help them to become better readers. Should we teachers be trying to 'fill the gap' - to do the things that some children experience at home before they've ever even set foot in a school? Or is it too late once they're in school? Does the school-based approach need to be different?