In this guest blog post, author Anna Hoghton explains how she researched a key motif in her debut novel for children and shares some of her findings. A great read for anyone who has read the book, or wants to, and for teachers who want to encourage children to research information for their own stories:

In this guest blog post, author Anna Hoghton explains how she researched a key motif in her debut novel for children and shares some of her findings. A great read for anyone who has read the book, or wants to, and for teachers who want to encourage children to research information for their own stories:Masks are clearly important in the world of my book – I mean, they’re in the title and on the front cover. Given that I was writing about Venice, I always knew I would use masks, it was just a question of how. What did I want masks to mean for my characters?

For inspiration, I investigated into how masks have been used throughout history. Masks have been used for centuries and the oldest mask ever found is from 7000 BC, though the art of mask making is likely to be even older than this. There are as many different styles of masks as there are different cultures and they’ve been used for everything: rituals, ceremonies, hunting, feasts, wars, in performances, theatres, fashion, art, sports, films, as well as for medical or protective reasons. Here are a few examples of how masks have been used by everyone from the ancient Greeks to Spiderman.

Ancient Greece

The iconic smiling comedy and frowning tragedy masks were used in ancient Greek theatre. Paired together, they showed the two extremes of the human psyche. Before this, Greeks also used masks in ceremonial rites and celebrations during the worship of Dionysus at Athens.

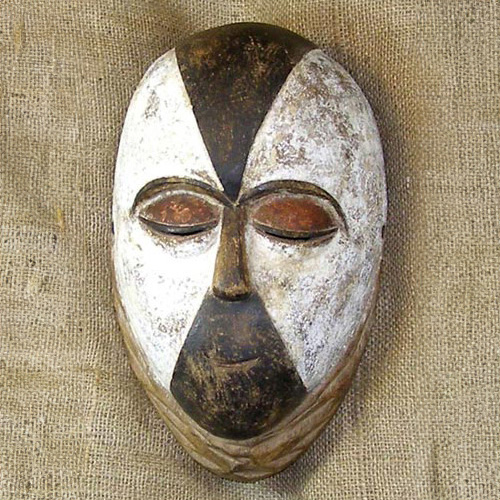

West Africa

In West Africa, masks are still used by some tribes (such as the Edo, Yoruba and Igbo cultures) as a way of communicating with ancestral spirits. These masks are skilfully made out of wood and often have human faces, though they are sometimes in the shapes of the animals. Some tribes believe that these animal masks allow them to communicate with the animal spirits of savannas and forests. Some tribes also use war masks with big eyes, angry expressions and bright colours to scare their enemies.

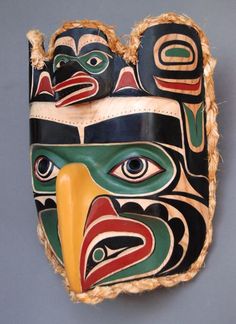

North America

In North America, the skilled woodworkers in coastal Inuit tribes make complex masks from wood, leather, bones and feathers. These masks are cleverly crafted, often with movable parts, and are very beautiful. Used in shamanic rituals, these masks represent the unity between the Inuit people, their ancestors and the animals that they hunt. When people are sick, the masks are also used to exorcize the evil spirits from them.

Oceania

In Oceania, where the culture of ancestral worship is very important, masks are made to represent ancestors. Sometimes these masks are enormous, even six metres high. They are also used to ward off evil spirits.

Latin America

Latin AmericaIn Latin America, Ancient Aztecs used masks to cover the faces of their deceased. At first these funeral masks were made from leather, but later they were made out of copper and gold.

Venice (of course I had to mention this one)

In the Republic of Venice, the concealment of identity was part of daily activity and used to break down social boundaries. This was useful as it meant state inquisitors could find out truths without citizens knowing who they were. But masks also meant that people could get up to no good... Eventually the wearing of masks in daily life was banned except for during certain months of the year.

In the Republic of Venice, the concealment of identity was part of daily activity and used to break down social boundaries. This was useful as it meant state inquisitors could find out truths without citizens knowing who they were. But masks also meant that people could get up to no good... Eventually the wearing of masks in daily life was banned except for during certain months of the year.However, masks continued to be used in the Commedia dell’Arte - an improvisational theatre that was popular until the 18th century. Their plays were based on established characters with a rough storyline, called Canovaccio. If you’ve read ‘The Mask of Aribella’ that name might sound familiar…

During the Black Death, plague doctor masks were also worn in Venice. These masks had long, white beaks, which were filled with sweet-smelling herbs and used to protect the wearer from breathing in infections, which at the time people believed to be airborne. I’ve used this iconic mask as the Mask Maker’s mask in ‘Aribella’.

Nowadays, masks are the fodder of superheroes such as Spiderman and Zorro who wear masks to protect their identities. Masks were used interestingly in the new ‘Watchmen’ TV series, which imagines a world where police also wear masks to protect their identities. There are several great lines, such as: "You can't heal under a mask [...] Wounds need air." and ‘Masks allow men to be cruel’.

So, in conclusion, masks can, and have, been used for many different purposes, even within a particular culture. I love the empowering, spiritual side of masks and decided to use masks in my story as a tool that could not only hide their wearers (by making them ‘unwatchable’), but also help them become more fully themselves and access the unique strengths inside of them. We all wear masks to greater or lesser extents in our lives. At the start of the novel, Aribella is hiding from the people around her. However, throughout the course of the book, she learns to trust her own power. When she eventually gets a mask of her own, one that is made for her, and puts it on, she knows she will never hide again. I think lots of young people could learn to trust themselves a little more and drop some of the false masks that we all hide behind in order to fit in. Imagine a world where we all fearlessly showed our true selves and unique powers? What a magical place that would be.

THE MASK OF ARIBELLA by Anna Hoghton is out now in paperback (£6.99, Chicken House)