Written before the announcement that schools will close to children other than those of key workers. I have also just heard that the council made the call to close the residential centre this afternoon, too.

And what if a child begins to display symptoms of COVID-19 in the middle of the night? I asked myself as I added to my risk assessment for our very imminent residential visit. I’d already imagined a scenario in which we didn’t have enough staff or children on the morning we were due to leave to make the visit viable.

At first the night time scenario seemed like the worst thing that could happen. But then I began to consider what would happen if a child or member of staff began to show symptoms during the day.

A member of staff would have to contact me, wherever I was: down a cave, climbing a gully, trekking though the Dales. Mobile phone reception isn’t exactly forthcoming out in the wilds of North Yorkshire.

I’d have to contact the school – with the same complications as above - who would then need to contact parents. Then what would happen? Would we ask parents to come and collect? Or should I ask the member of staff who had brought a car to take them home? But what if it was more than one child? Should I actually be taking the school minibus so that I could return poorly children to school as quickly as possible?

And what if it was members of staff who came down with something? Would we be left with insufficient ratios to really safeguard the children on an outward bound adventure holiday? Would we call on other staff from school to join us? But what if school had begun to experience staff absences? I didn’t even consider what might have to happen if I – the one who had spent endless hours planning the visit – got ill. Did anyone else know enough about the ins and outs of the residential to be able to run it in my absence?

So many questions. No encouraging answers. In my mind I came to the conclusion that if a child or adult developed a dry cough or a high temperature, I’d have to get them home as quickly as possible, followed swiftly by the rest of the children. If one child had it, then how many others might have been infected during the stay?

The evening after completing a risk assessment which had led me to believe that actually, this residential was quite a risk – one I was not happy to shoulder the burden of, the government upped the ante with their advice. The words ‘non-essential’ were used several times. Although I totally believe in the importance of such an experience for children living in the city, I was pretty sure it fell into the ‘non-essential’ category.

Sir, is the residential still on? I was asked by eager children the following morning. They were aware of the fragility of the chance of it going ahead. I had to give disappointingly non-committal answers – I didn’t want to cause undue upset. I was asked the same question by parents on the gate – some of whom wanted to know when they should start packing, others expressed their own concerns.

But I had found myself at a standstill. I thought I should cancel the trip, but that would risk a financial loss to the school. Should I wait for the venue to cancel, or should I go ahead? I spoke to the deputy of another school who were going to the same venue as us during the same week – he was in the same position.

I came clean with the manager of the venue: we were worried about the risks but didn’t want to lose the money – he was honest with me: they too were waiting for further guidance on school closure as to whether they were going to cancel forthcoming visits. I broached the subject of a postponement and requested potential dates for next academic year for the same cohort of children.

The happy ending to this story is that our trust’s early start date in August meant that we could find an early September slot that no other school would be able to take. All being well, the children will get to experience the great outdoors together for three days, albeit in six months’ time. We are all disappointed that although schools remain open, we won’t get our residential this year but safety comes first. A decision which puts the health and wellbeing of children and staff first is the best decision.

Wednesday, 18 March 2020

Sunday, 15 March 2020

School Leadership: Hard or Complex?

Saturday, 15 February 2020

Getting Ready For The 2021 KS2 Reading Test (or 16 Reading Texts and SATs-Style Question Papers)

This blog post is now available at:

The question papers, texts and mark schemes are available at:

Labels:

comprehension,

ks2 sats,

reading,

reading comprehension,

reading lesson,

SATs,

SATs ks2

Monday, 10 February 2020

Friday, 17 January 2020

Guest Blog Post: The World of Masks by Anna Hoghton

Click here to read my review of The Mask of Aribella by Anna Hoghton.

In this guest blog post, author Anna Hoghton explains how she researched a key motif in her debut novel for children and shares some of her findings. A great read for anyone who has read the book, or wants to, and for teachers who want to encourage children to research information for their own stories:

In this guest blog post, author Anna Hoghton explains how she researched a key motif in her debut novel for children and shares some of her findings. A great read for anyone who has read the book, or wants to, and for teachers who want to encourage children to research information for their own stories:

Masks are clearly important in the world of my book – I mean, they’re in the title and on the front cover. Given that I was writing about Venice, I always knew I would use masks, it was just a question of how. What did I want masks to mean for my characters?

For inspiration, I investigated into how masks have been used throughout history. Masks have been used for centuries and the oldest mask ever found is from 7000 BC, though the art of mask making is likely to be even older than this. There are as many different styles of masks as there are different cultures and they’ve been used for everything: rituals, ceremonies, hunting, feasts, wars, in performances, theatres, fashion, art, sports, films, as well as for medical or protective reasons. Here are a few examples of how masks have been used by everyone from the ancient Greeks to Spiderman.

Ancient Greece

The iconic smiling comedy and frowning tragedy masks were used in ancient Greek theatre. Paired together, they showed the two extremes of the human psyche. Before this, Greeks also used masks in ceremonial rites and celebrations during the worship of Dionysus at Athens.

West Africa

In West Africa, masks are still used by some tribes (such as the Edo, Yoruba and Igbo cultures) as a way of communicating with ancestral spirits. These masks are skilfully made out of wood and often have human faces, though they are sometimes in the shapes of the animals. Some tribes believe that these animal masks allow them to communicate with the animal spirits of savannas and forests. Some tribes also use war masks with big eyes, angry expressions and bright colours to scare their enemies.

North America

In North America, the skilled woodworkers in coastal Inuit tribes make complex masks from wood, leather, bones and feathers. These masks are cleverly crafted, often with movable parts, and are very beautiful. Used in shamanic rituals, these masks represent the unity between the Inuit people, their ancestors and the animals that they hunt. When people are sick, the masks are also used to exorcize the evil spirits from them.

Oceania

In Oceania, where the culture of ancestral worship is very important, masks are made to represent ancestors. Sometimes these masks are enormous, even six metres high. They are also used to ward off evil spirits.

Latin America

Latin America

In Latin America, Ancient Aztecs used masks to cover the faces of their deceased. At first these funeral masks were made from leather, but later they were made out of copper and gold.

Venice (of course I had to mention this one)

In the Republic of Venice, the concealment of identity was part of daily activity and used to break down social boundaries. This was useful as it meant state inquisitors could find out truths without citizens knowing who they were. But masks also meant that people could get up to no good... Eventually the wearing of masks in daily life was banned except for during certain months of the year.

In the Republic of Venice, the concealment of identity was part of daily activity and used to break down social boundaries. This was useful as it meant state inquisitors could find out truths without citizens knowing who they were. But masks also meant that people could get up to no good... Eventually the wearing of masks in daily life was banned except for during certain months of the year.

However, masks continued to be used in the Commedia dell’Arte - an improvisational theatre that was popular until the 18th century. Their plays were based on established characters with a rough storyline, called Canovaccio. If you’ve read ‘The Mask of Aribella’ that name might sound familiar…

During the Black Death, plague doctor masks were also worn in Venice. These masks had long, white beaks, which were filled with sweet-smelling herbs and used to protect the wearer from breathing in infections, which at the time people believed to be airborne. I’ve used this iconic mask as the Mask Maker’s mask in ‘Aribella’.

Nowadays, masks are the fodder of superheroes such as Spiderman and Zorro who wear masks to protect their identities. Masks were used interestingly in the new ‘Watchmen’ TV series, which imagines a world where police also wear masks to protect their identities. There are several great lines, such as: "You can't heal under a mask [...] Wounds need air." and ‘Masks allow men to be cruel’.

So, in conclusion, masks can, and have, been used for many different purposes, even within a particular culture. I love the empowering, spiritual side of masks and decided to use masks in my story as a tool that could not only hide their wearers (by making them ‘unwatchable’), but also help them become more fully themselves and access the unique strengths inside of them. We all wear masks to greater or lesser extents in our lives. At the start of the novel, Aribella is hiding from the people around her. However, throughout the course of the book, she learns to trust her own power. When she eventually gets a mask of her own, one that is made for her, and puts it on, she knows she will never hide again. I think lots of young people could learn to trust themselves a little more and drop some of the false masks that we all hide behind in order to fit in. Imagine a world where we all fearlessly showed our true selves and unique powers? What a magical place that would be.

THE MASK OF ARIBELLA by Anna Hoghton is out now in paperback (£6.99, Chicken House)

In this guest blog post, author Anna Hoghton explains how she researched a key motif in her debut novel for children and shares some of her findings. A great read for anyone who has read the book, or wants to, and for teachers who want to encourage children to research information for their own stories:

In this guest blog post, author Anna Hoghton explains how she researched a key motif in her debut novel for children and shares some of her findings. A great read for anyone who has read the book, or wants to, and for teachers who want to encourage children to research information for their own stories:Masks are clearly important in the world of my book – I mean, they’re in the title and on the front cover. Given that I was writing about Venice, I always knew I would use masks, it was just a question of how. What did I want masks to mean for my characters?

For inspiration, I investigated into how masks have been used throughout history. Masks have been used for centuries and the oldest mask ever found is from 7000 BC, though the art of mask making is likely to be even older than this. There are as many different styles of masks as there are different cultures and they’ve been used for everything: rituals, ceremonies, hunting, feasts, wars, in performances, theatres, fashion, art, sports, films, as well as for medical or protective reasons. Here are a few examples of how masks have been used by everyone from the ancient Greeks to Spiderman.

Ancient Greece

The iconic smiling comedy and frowning tragedy masks were used in ancient Greek theatre. Paired together, they showed the two extremes of the human psyche. Before this, Greeks also used masks in ceremonial rites and celebrations during the worship of Dionysus at Athens.

West Africa

In West Africa, masks are still used by some tribes (such as the Edo, Yoruba and Igbo cultures) as a way of communicating with ancestral spirits. These masks are skilfully made out of wood and often have human faces, though they are sometimes in the shapes of the animals. Some tribes believe that these animal masks allow them to communicate with the animal spirits of savannas and forests. Some tribes also use war masks with big eyes, angry expressions and bright colours to scare their enemies.

North America

In North America, the skilled woodworkers in coastal Inuit tribes make complex masks from wood, leather, bones and feathers. These masks are cleverly crafted, often with movable parts, and are very beautiful. Used in shamanic rituals, these masks represent the unity between the Inuit people, their ancestors and the animals that they hunt. When people are sick, the masks are also used to exorcize the evil spirits from them.

Oceania

In Oceania, where the culture of ancestral worship is very important, masks are made to represent ancestors. Sometimes these masks are enormous, even six metres high. They are also used to ward off evil spirits.

Latin America

Latin AmericaIn Latin America, Ancient Aztecs used masks to cover the faces of their deceased. At first these funeral masks were made from leather, but later they were made out of copper and gold.

Venice (of course I had to mention this one)

In the Republic of Venice, the concealment of identity was part of daily activity and used to break down social boundaries. This was useful as it meant state inquisitors could find out truths without citizens knowing who they were. But masks also meant that people could get up to no good... Eventually the wearing of masks in daily life was banned except for during certain months of the year.

In the Republic of Venice, the concealment of identity was part of daily activity and used to break down social boundaries. This was useful as it meant state inquisitors could find out truths without citizens knowing who they were. But masks also meant that people could get up to no good... Eventually the wearing of masks in daily life was banned except for during certain months of the year.However, masks continued to be used in the Commedia dell’Arte - an improvisational theatre that was popular until the 18th century. Their plays were based on established characters with a rough storyline, called Canovaccio. If you’ve read ‘The Mask of Aribella’ that name might sound familiar…

During the Black Death, plague doctor masks were also worn in Venice. These masks had long, white beaks, which were filled with sweet-smelling herbs and used to protect the wearer from breathing in infections, which at the time people believed to be airborne. I’ve used this iconic mask as the Mask Maker’s mask in ‘Aribella’.

Nowadays, masks are the fodder of superheroes such as Spiderman and Zorro who wear masks to protect their identities. Masks were used interestingly in the new ‘Watchmen’ TV series, which imagines a world where police also wear masks to protect their identities. There are several great lines, such as: "You can't heal under a mask [...] Wounds need air." and ‘Masks allow men to be cruel’.

So, in conclusion, masks can, and have, been used for many different purposes, even within a particular culture. I love the empowering, spiritual side of masks and decided to use masks in my story as a tool that could not only hide their wearers (by making them ‘unwatchable’), but also help them become more fully themselves and access the unique strengths inside of them. We all wear masks to greater or lesser extents in our lives. At the start of the novel, Aribella is hiding from the people around her. However, throughout the course of the book, she learns to trust her own power. When she eventually gets a mask of her own, one that is made for her, and puts it on, she knows she will never hide again. I think lots of young people could learn to trust themselves a little more and drop some of the false masks that we all hide behind in order to fit in. Imagine a world where we all fearlessly showed our true selves and unique powers? What a magical place that would be.

THE MASK OF ARIBELLA by Anna Hoghton is out now in paperback (£6.99, Chicken House)

Labels:

children's books,

children's literature,

guest post

Thursday, 16 January 2020

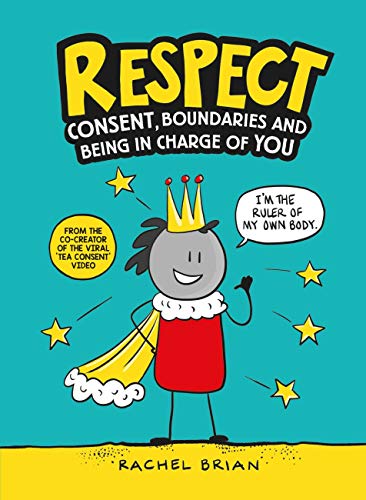

Book Review: Respect: Consent, Boundaries and Being in Charge of YOU by Rachel Brian

When a book is pounced upon and read within moments of it entering the house, it is fairly indicative of a good book. Sure, it means that someone is judging by the cover, but I believe that is why publishers, illustrators, authors and such other folk really spend time on getting the cover right.

When a book is then read by the entire household in quick succession you get another sense of its importance: it wasn't just the cover that worked but the contents too. And given that Rachel Brian (co-creator of the viral Tea Consent video and the follow-up Consent For Kids) is responsible not only for the cover but for the innards of this book, that's two marks for her.

However, there is something even more special about a book entering the house and being read by all members of the family: when you are really hoping that it is read and digested and it is. You see, Rachel Brian's new book is called 'Respect' and it is about 'consent, boundaries and being in charge of you'. When you have three children growing up in a world which has recently shed light on how terribly people can be exploited by others, it's good to know that there are child-friendly resources available to help to protect them.

In no uncertain terms, this book uses language and pictures which appeal directly to children to give a slow walk through exactly what is meant by consent. The thrust of the book is that we can make our own choices about what happens to our bodies. 'Respect' doesn't refer to sex (the closest thing it gets to this is a panel about taking and sharing pictures of people under 18 with no clothes on); instead, the focus is on more every-day scenarios where we have a choice about our own bodies.

The book also contains an all-important chapter about respecting other people's boundaries. It could be argued that this is the most crucial part of the book: it places the responsibility on us to control our own actions rather than expecting others to take preventative measures against our potential non-consensual actions. Another chapter focuses on what the reader can do if they witness abuse of someone else.

With many a humourous touch, a whole host of funky cartoons and some exceedingly sensitively-written text, this book is an essential read for... well, pretty much everyone, old and young alike. It's the sort of thing teachers and parents should be jumping at the chance to read with their children - and the children won't be complaining either. Not many books exist like this - many books about such issues can be a bit twee, or don't contain enough to appeal to the intended audience - so I welcome this little book with open arms and hope that there are more where it came from.

WREN & ROOK | £7.99 | HARDBACK | 9TH JANUARY 2020

When a book is then read by the entire household in quick succession you get another sense of its importance: it wasn't just the cover that worked but the contents too. And given that Rachel Brian (co-creator of the viral Tea Consent video and the follow-up Consent For Kids) is responsible not only for the cover but for the innards of this book, that's two marks for her.

However, there is something even more special about a book entering the house and being read by all members of the family: when you are really hoping that it is read and digested and it is. You see, Rachel Brian's new book is called 'Respect' and it is about 'consent, boundaries and being in charge of you'. When you have three children growing up in a world which has recently shed light on how terribly people can be exploited by others, it's good to know that there are child-friendly resources available to help to protect them.

In no uncertain terms, this book uses language and pictures which appeal directly to children to give a slow walk through exactly what is meant by consent. The thrust of the book is that we can make our own choices about what happens to our bodies. 'Respect' doesn't refer to sex (the closest thing it gets to this is a panel about taking and sharing pictures of people under 18 with no clothes on); instead, the focus is on more every-day scenarios where we have a choice about our own bodies.

The book also contains an all-important chapter about respecting other people's boundaries. It could be argued that this is the most crucial part of the book: it places the responsibility on us to control our own actions rather than expecting others to take preventative measures against our potential non-consensual actions. Another chapter focuses on what the reader can do if they witness abuse of someone else.

With many a humourous touch, a whole host of funky cartoons and some exceedingly sensitively-written text, this book is an essential read for... well, pretty much everyone, old and young alike. It's the sort of thing teachers and parents should be jumping at the chance to read with their children - and the children won't be complaining either. Not many books exist like this - many books about such issues can be a bit twee, or don't contain enough to appeal to the intended audience - so I welcome this little book with open arms and hope that there are more where it came from.

WREN & ROOK | £7.99 | HARDBACK | 9TH JANUARY 2020

Labels:

Book review,

book reviews,

children's books,

consent,

pshce,

pshe

Saturday, 4 January 2020

Book Review: 'The Mask Of Aribella' by Anna Hoghton

Choosing the islands and lagoon of Venice for the setting of a magial middle grade escapade was a stroke of genius. The surrealness of such a location makes the events of the story seem entirely plausible: very surely an only-just teenager in that strange place could find out they are a member of a magical order and that actually, they are the one to avert the catastrophe that is looming over the people of Venice.

It's on the eve of Aribella's 13th birthday that, in a fit of rage, she discovers she has the power to conjure fire. Very quickly she is whisked away into an ever-present but invisible parallel world where she discovers there is more to her unique city than meets the eye. But it is clear that not all is well, and is the way with such tales, she finds it is up to her and her new-found friends to save the day.

With the odd hint of certain giants of the genre, albeit with an Italian twist, this story is bound to enchant anyone within just a few pages. The story skims along at a cracking pace, yet, just as with the wooden piles on which Venice is built, there are foundations that run deep - the power of friendship and family, trust and responsibility provide a solid base for this dark tale of good versus evil.

Not only is this a fantasy adventure, it will also have its readers guessing whodunnit-style as to who is really responsible for the sinister goings on. As I read, I mentally drew up my own list of suspects and weighed up their motives, questioning their behaviour and coming to my own conclusions about who is behind the appearance of spectres in the lagoon, the disappearance of all the animals and the too-regular appearance of the Blood Moon. I, of course, was wrong, but that made the ending all the more satisfying - and there was more than one goosebump moments as the elements of the plot came together in the final moments.

A strong start for children's publishing in 2020 and a great introduction to Anna Hoghton, a new voice in children's fiction.

Published by Chicken House · 2nd January 2020 · Paperback · £6.99 · 9+ year olds

It's on the eve of Aribella's 13th birthday that, in a fit of rage, she discovers she has the power to conjure fire. Very quickly she is whisked away into an ever-present but invisible parallel world where she discovers there is more to her unique city than meets the eye. But it is clear that not all is well, and is the way with such tales, she finds it is up to her and her new-found friends to save the day.

With the odd hint of certain giants of the genre, albeit with an Italian twist, this story is bound to enchant anyone within just a few pages. The story skims along at a cracking pace, yet, just as with the wooden piles on which Venice is built, there are foundations that run deep - the power of friendship and family, trust and responsibility provide a solid base for this dark tale of good versus evil.

Not only is this a fantasy adventure, it will also have its readers guessing whodunnit-style as to who is really responsible for the sinister goings on. As I read, I mentally drew up my own list of suspects and weighed up their motives, questioning their behaviour and coming to my own conclusions about who is behind the appearance of spectres in the lagoon, the disappearance of all the animals and the too-regular appearance of the Blood Moon. I, of course, was wrong, but that made the ending all the more satisfying - and there was more than one goosebump moments as the elements of the plot came together in the final moments.

A strong start for children's publishing in 2020 and a great introduction to Anna Hoghton, a new voice in children's fiction.

Published by Chicken House · 2nd January 2020 · Paperback · £6.99 · 9+ year olds

Thursday, 2 January 2020

Book Review: 'Empire's End - A Roman Story' by Leila Rasheed

There are over 30 other books in Goodreads' Roman Britain in YA & Middle Grade Fiction Listopia list, some by eminent writers such as Rosemary Sutcliff. So why do we need another book which falls into this (very niche) category?

Well, Leila Rasheed has an important story to tell. Scholastic's Voices series focuses specifically on 'the unsung voices of our past' - in this particular book it's the voice of a young Libyan Roman woman who finds herself at the empire's end - in Britain. She has accompanied her father, a doctor, who is an aide to Septimius Severus, a Roman Emperor originally from Libya, and his powerful and influential Syrian wife, Julia Domna.

Not only do we get a much more diverse cast than in other historical novels, and are allowed to hear the stories of those who history doesn't always like to remember, but we also hear it from the pen of an author who herself grew up in Libya and who describes herself (on her Twitter bio at least) as British-Asian European.

CLPE's Reflecting Realities survey of ethnic representation in UK children's books found that in 2018 only 4% of children's books published featured a Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) main protagonist. The BookTrust Represents research into representation of people of colour among children’s book authors and illustrators found that in 2017 less than 6% of book creators were from a BAME background. That's why we need this book.

But this doesn't just fill a void in the market, this is a seriously good book. The gripping and fast-paced story is all carefully interwoven with historical fact: a Roman emperor from Libya did live and die in York, archaeological research has shown that those with black African heritage did live in Britain during the Roman period and that people from all over the Roman provinces ended up marrying each other and having children.

In 'Empire's End' Rasheed imagines how one such character may have ended up in Britain, despite having been born in North Africa. Although slavery is a key theme in the book, it is important that we follow the story of a high status a BAME character - as we've mentioned before, it is these stories that are seldom told. As Camilla's destiny is linked to that of the struggle for power in the Roman Empire, nothing is very certain for her as she travels the world and settles in a place that seems as far from home as she can imagine. The story twists and turns, painting vivid characters and their realities in a human way against the backdrop of one of the Roman Empire's trickiest times.

Young readers will be thrilled to find this combination of qualities in one fairly short story which is bound to hold the attention of even the most flighty of readers. And with this being the fourth book in the series, there is already plenty for readers to go back and discover. A fantastic first read for 2020.

Well, Leila Rasheed has an important story to tell. Scholastic's Voices series focuses specifically on 'the unsung voices of our past' - in this particular book it's the voice of a young Libyan Roman woman who finds herself at the empire's end - in Britain. She has accompanied her father, a doctor, who is an aide to Septimius Severus, a Roman Emperor originally from Libya, and his powerful and influential Syrian wife, Julia Domna.

Not only do we get a much more diverse cast than in other historical novels, and are allowed to hear the stories of those who history doesn't always like to remember, but we also hear it from the pen of an author who herself grew up in Libya and who describes herself (on her Twitter bio at least) as British-Asian European.

CLPE's Reflecting Realities survey of ethnic representation in UK children's books found that in 2018 only 4% of children's books published featured a Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) main protagonist. The BookTrust Represents research into representation of people of colour among children’s book authors and illustrators found that in 2017 less than 6% of book creators were from a BAME background. That's why we need this book.

But this doesn't just fill a void in the market, this is a seriously good book. The gripping and fast-paced story is all carefully interwoven with historical fact: a Roman emperor from Libya did live and die in York, archaeological research has shown that those with black African heritage did live in Britain during the Roman period and that people from all over the Roman provinces ended up marrying each other and having children.

In 'Empire's End' Rasheed imagines how one such character may have ended up in Britain, despite having been born in North Africa. Although slavery is a key theme in the book, it is important that we follow the story of a high status a BAME character - as we've mentioned before, it is these stories that are seldom told. As Camilla's destiny is linked to that of the struggle for power in the Roman Empire, nothing is very certain for her as she travels the world and settles in a place that seems as far from home as she can imagine. The story twists and turns, painting vivid characters and their realities in a human way against the backdrop of one of the Roman Empire's trickiest times.

Young readers will be thrilled to find this combination of qualities in one fairly short story which is bound to hold the attention of even the most flighty of readers. And with this being the fourth book in the series, there is already plenty for readers to go back and discover. A fantastic first read for 2020.

Sunday, 22 December 2019

Book Review: 'The Star Outside My Window' by Onjali Q. Rauf

As an adult reader, I found this book a difficult one to read - difficult but compelling, yet strangely heartwarming. However, what is apparent to grown ups will certainly be less so for younger readers - the age range the book is really intended for.

The difficult thing about it is that the clues are all there as to what Aniyah and Noah have been through prior to the events in the story. I remember saying when Lisa Thompson's 'The Light Jar' was published that I hadn't encountered themes of domestic violence in a children's book before - in The Star Outside My Window it is a much more central theme.

In its plot, there are definite reminders of Onjali's previous book 'The Boy At The Back Of The Class' - a group of optmistic children hatch a hare-brained, heart-filled scheme to ensure that justice is done. Aniyah, Noah and their new foster brothers Ben and Travis, run away on Halloween and head to London to gate-crash the naming ceremony of a brand new star which is travelling closer to earth than any other star has before.

With the scientific element of the story being quite fantastical, and the terrible realities of domestic violence being ever present, a balance is created. Aniyah's love of astronomy brings another dimension too - there are plenty of great factoids scattered throughout the story. But it is the narrator's voice which really sets this story firmly in place as appropriate for the intended age group despite its upsetting premise. The child's point of view which Rauf adopts, and carries off so well (as she also did in her first book), makes for a gentle and palatable yet serious treatment of the subject matter.

Books which tackle ideas about what happens after death are usually problematic: more often than not, they push one particular, definite idea or another - beliefs which definitely wouldn't align with everyone's way of thinking, therefore alienating potential readers. In 'The Star Outside My Window' a new precendent is set: all it portrays is one child's own rationalisation of what they think has happened to their mum - an idea forged in the furnaces of grief and the only thing that makes sense to them at the time. The author pushes no religious or secular beliefs, she just tells the story of one little girl, struggling to come to terms with what has happened.

And whilst the bulk of this review has focused on the deep and meaningfuls of this book, it really must be said that it is a rip-roaring, heart-in-mouth adventure too - will they really make it all the way to the Royal Observatory, Greenwich from Waverley Village in Oxfordshire in time without being caught? The odds are stacked against them but you'll cheer repeatedly as they thwart well-meaning citizens who only want to keep them safe, and you'll laugh as squirrels - yes, squirrels! - pretty much save the day in the nick of time.

This certainly is one of 2019's must-read books, but perhaps one that parents and teachers might want to exercise caution with. To help with potential upset, and to promote growth of empathy, the book actually contains a few helpful sections pre- and postscript about the nature of the story and domestic abuse, as well as information for how to get help if aspects of the story ring true for its readers - a thoughtful and essential addition to this brave new book.

Orion Children's Books - 3rd October 2019 - Price: £6.99 - ISBN-13: 9781510105140

The difficult thing about it is that the clues are all there as to what Aniyah and Noah have been through prior to the events in the story. I remember saying when Lisa Thompson's 'The Light Jar' was published that I hadn't encountered themes of domestic violence in a children's book before - in The Star Outside My Window it is a much more central theme.

In its plot, there are definite reminders of Onjali's previous book 'The Boy At The Back Of The Class' - a group of optmistic children hatch a hare-brained, heart-filled scheme to ensure that justice is done. Aniyah, Noah and their new foster brothers Ben and Travis, run away on Halloween and head to London to gate-crash the naming ceremony of a brand new star which is travelling closer to earth than any other star has before.

With the scientific element of the story being quite fantastical, and the terrible realities of domestic violence being ever present, a balance is created. Aniyah's love of astronomy brings another dimension too - there are plenty of great factoids scattered throughout the story. But it is the narrator's voice which really sets this story firmly in place as appropriate for the intended age group despite its upsetting premise. The child's point of view which Rauf adopts, and carries off so well (as she also did in her first book), makes for a gentle and palatable yet serious treatment of the subject matter.

Books which tackle ideas about what happens after death are usually problematic: more often than not, they push one particular, definite idea or another - beliefs which definitely wouldn't align with everyone's way of thinking, therefore alienating potential readers. In 'The Star Outside My Window' a new precendent is set: all it portrays is one child's own rationalisation of what they think has happened to their mum - an idea forged in the furnaces of grief and the only thing that makes sense to them at the time. The author pushes no religious or secular beliefs, she just tells the story of one little girl, struggling to come to terms with what has happened.

And whilst the bulk of this review has focused on the deep and meaningfuls of this book, it really must be said that it is a rip-roaring, heart-in-mouth adventure too - will they really make it all the way to the Royal Observatory, Greenwich from Waverley Village in Oxfordshire in time without being caught? The odds are stacked against them but you'll cheer repeatedly as they thwart well-meaning citizens who only want to keep them safe, and you'll laugh as squirrels - yes, squirrels! - pretty much save the day in the nick of time.

This certainly is one of 2019's must-read books, but perhaps one that parents and teachers might want to exercise caution with. To help with potential upset, and to promote growth of empathy, the book actually contains a few helpful sections pre- and postscript about the nature of the story and domestic abuse, as well as information for how to get help if aspects of the story ring true for its readers - a thoughtful and essential addition to this brave new book.

Orion Children's Books - 3rd October 2019 - Price: £6.99 - ISBN-13: 9781510105140

Thursday, 12 December 2019

Beware The Reverse-Engineered Curriculum (or The Potential Pitfalls Of Going For Retrieval Practice Pell-Mell)

This blog post is now available at:

Monday, 2 December 2019

Including Word Etymology On Knowledge Organisers

This blog post is now available at https://www.aidansevers.com/post/including-word-etymology-on-knowledge-organisers

Friday, 29 November 2019

History Key Questions To Ask When Learning About A Person, Event or Period in KS1

This blog post is now available at:

Labels:

curriculum,

curriculum development,

history,

KS1,

national curriculum

Tuesday, 19 November 2019

#Lollies2020: Joshua Seigal - 'I Bet I Can Make You Laugh'

When I was asked to champion one of the books nominated for the Lollies 2020 book awards, there was really only one choice for me: Joshua Seigal's 'I Bet I Can Make You Laugh'. My middle daughter (I have three) is an avid reader (I mean really avid) and, amongst other things, she is partial to both funny books and poetry. So when a copy of Joshua Seigal's 'I Bet I Can Make You Laugh' which I won (and is signed) dropped through our letterbox, she pounced upon it and devoured it.

And it's regularly off the bookshelf for a quick read, which, as avid readers among you will know, often turns into a long read (I'm not complaining). With poems from Joshua himself, as well as a range of other poets such as A.F. Harrold, Sue Hardy-Dawson, Frank Dixon (aged 7), Irene Assiba D'Almeida, Alfred Noyes, Lewis Carroll, Kat Francois, Andy Seed and Jay Hulme, this collection really willmost probably, almost certainly make you laugh - if you're an adult. If you're a child, there's no doubt about it: you will laugh.

And if you don't believe me (and I'm so excited about this), here's a brand new poem from Joshua Seigal to give you a taste of what's to come if you get your hands on a copy of Lollies 2020 nominated book 'I Bet I Can Make You Laugh'. I cheekily asked that he pen something new especially for my blog and here it is: a funny Shakesperean sonnet (go on, count the lines and try reading it in iambic pentameter)!

The Ferocious Commotion

A ferocious commotion’s occurring next door.

It’s like ten thousand buffalo having a fight

It’s as loud as the crash of a rusty chainsaw

and I know it’ll keep me awake half the night.

Like the whistling whoosh of a runaway train,

a ferocious commotion’s occurring next door.

Like a hideous gargoyle yelling in pain,

it’s as loud as a battlefield, loud as a war.

It roars like a lion that’s stepped on a pin.

It clanks like a tank that’s got stuck in the mud.

It shrieks like a shark when you tickle its fin

with a hoot and a honk and a bang and a thud.

What on earth is it? I go exploring

and discover it’s only my grandfather snoring.

www.joshuaseigal.co.uk

Tuesday, 22 October 2019

In Praise Of The Written Lesson Evaluation (And The Motivating Power Of Success)

Remember when, as a trainee, you had to have that pristine file (or two) that contained all your paperwork? I can't even remember what on earth all that junk was, only that I was constantly in trouble with my tutors for not having my file up-to-date.

What I do remember, and resent, was the lesson evaluations that we were supposed to write. Inevitably, after a day full of teaching and an evening full of planning (repeat ad nauseam), they were never filled in whilst the lesson was fresh in my mind.

Well, 13 or so years after finishing my degree I've finally discovered that written evaluations actually can be quite useful.

The other day, after working with a group who had been selected as ones who would potentially struggle with a research and present task, I resorted to writing down some thoughts after a somewhat difficult time with them. Here's exactly what I wrote in my notebook that lunchtime:

Not a Torture, But a Joy (principle of the Kodaly Concept)

Today was not a joy. It was torture for all involved. 'Pulling teeth' was the phrase used by the head who overheard me 'teaching'. I was tortured by the lack of interest and engagement, as were the children (who were tortured by my frustration).

The task - research and present - has been dragging on for a few weeks now. Every session I scaffold the time and activity even more to try to combat the inactivity. But there is no drive, no determination, no will to research and present. It's not, I think, that the ancient civilisation of the Indus Valley means nothing to them, but that reading books, locating information and then preparing to re-present that information does not interest them.

I'm also fairly sure that the children in my group, selected for this very reason, don't know how to carry out such a process. This lack of skill has led to past experiences where they have felt unsuccessful in such a task - I assume. And this lack of feeling of success, I reason, must have led to the lack of desire to make an effort today.

I talk so often of 'lack'. I see that they need to experience success. Must some success be my main goal, then? By what means? What must I jettison in order to gain this success? Must we put something aside, at least for now, in order to gain what they currently lack: success, motivation, confidence.

A tentative yes - I must prioritise their experience of success over what I am currently trying to get out of them. And what is that? The skill of reading for a purpose: gaining knowledge. The skill of writing coherent sentences, paragraphs, texts in order for them to then present it verbally.

What will I give, then? How will I ensure that what I give provides them with something from which they can derive the experience of success, without attributing all the success to me and my provision?

What if I asked them what they wanted? Would that reveal what they are truly motivated to do?

Beyond this particular piece of work, how can learning become a joy rather than a torture for these children?

Next session:

What I do remember, and resent, was the lesson evaluations that we were supposed to write. Inevitably, after a day full of teaching and an evening full of planning (repeat ad nauseam), they were never filled in whilst the lesson was fresh in my mind.

Well, 13 or so years after finishing my degree I've finally discovered that written evaluations actually can be quite useful.

The other day, after working with a group who had been selected as ones who would potentially struggle with a research and present task, I resorted to writing down some thoughts after a somewhat difficult time with them. Here's exactly what I wrote in my notebook that lunchtime:

Not a Torture, But a Joy (principle of the Kodaly Concept)

Today was not a joy. It was torture for all involved. 'Pulling teeth' was the phrase used by the head who overheard me 'teaching'. I was tortured by the lack of interest and engagement, as were the children (who were tortured by my frustration).

The task - research and present - has been dragging on for a few weeks now. Every session I scaffold the time and activity even more to try to combat the inactivity. But there is no drive, no determination, no will to research and present. It's not, I think, that the ancient civilisation of the Indus Valley means nothing to them, but that reading books, locating information and then preparing to re-present that information does not interest them.

I'm also fairly sure that the children in my group, selected for this very reason, don't know how to carry out such a process. This lack of skill has led to past experiences where they have felt unsuccessful in such a task - I assume. And this lack of feeling of success, I reason, must have led to the lack of desire to make an effort today.

I talk so often of 'lack'. I see that they need to experience success. Must some success be my main goal, then? By what means? What must I jettison in order to gain this success? Must we put something aside, at least for now, in order to gain what they currently lack: success, motivation, confidence.

A tentative yes - I must prioritise their experience of success over what I am currently trying to get out of them. And what is that? The skill of reading for a purpose: gaining knowledge. The skill of writing coherent sentences, paragraphs, texts in order for them to then present it verbally.

What will I give, then? How will I ensure that what I give provides them with something from which they can derive the experience of success, without attributing all the success to me and my provision?

What if I asked them what they wanted? Would that reveal what they are truly motivated to do?

Beyond this particular piece of work, how can learning become a joy rather than a torture for these children?

Next session:

- group discussion: ides for the presentation

- finish off revision of text - teacher-led/modelled

- edit text - shared work

- back to organisation of presentation - what needs to be done? Assign roles

- children prepare presentation; teacher to provide assistance where needed

4 and 5 rely on 1. 2 and 3 should be inspired by 1. If the children are motivated by their own decisions about the presentation they will hopefully be more motivated to get the script right.

Let's see...

After some more thought (those moments of solitude - in the car, on my bike, in the shower - can always be relied upon for further reflection and inspiration) I decided that I would complete steps 2 and 3 myself, bringing a complete script, informed mostly by their reading and notes, to the next session.

I sat down with the group and showed them the script I'd brought. We read it through. They recognised that the majority of it was their hard-won work and, seeing it all typed up, seemed pleased with what they had, with my help, produced. They fell to assigning parts of the script with gusto and, impressively, no arguments - everyone got the bit they wanted to say (nearly all of them chose to present the information they had researched and contributed to the script - a sign of ownership and pride, I think).

They began to rehearse it, ad-libbing and adding new bits in to make it more of a presentation and less of a standing-up-and-reading-from-a-piece-of-paper affair. Some of them even set about learning their part by heart (which they succeeded in doing). One particular child who often finds it difficult to focus for various, real reasons, took a lead role and did a great job of organising the team. They decided they needed visuals and went off to find some big paper (they agreed to avoid powerpoint as they had previously presented work in this way). They returned with a roll of paper and decided to make a long poster which followed the timeline of the script. Accepting my suggestion, they used some of the research materials I had prepared, cutting out relevant images to display based on the content of the script. They practised - I'll admit it was rowdy at time - and when the day finally came, they presented confidently (even if nerves did lead to very quick speaking) and proudly to their gathered parents.

I'm glad I didn't press on with forcing them to revise and edit the text as a group - I think I made the right decision to finish that bit myself in order to move them onto something that they would get a little more gratification out of. By completing everything I outlined in the last paragraph, the group surely felt motivated by their little successes.

Here's to hoping that next time, buoyed by this experience, they will feel more motivated to complete similar tasks - that is, if I actually decide to inflict that upon them again! Research and present is a little dry...

Wednesday, 2 October 2019

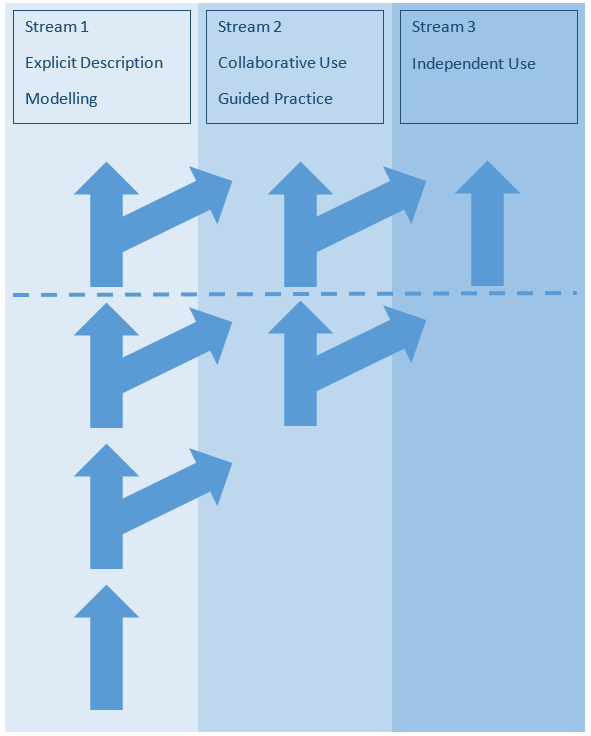

Responsiveness and the Release of Responsibility (A Model)

This article is now available at my website:

Labels:

education,

learning sequences,

lesson plan,

Lessons,

planning,

teaching,

teaching sequence

Friday, 27 September 2019

Prioritising Positivity in Leadership

This blog post is now available at https://www.aidansevers.com/blog

If you would like Aidan to work with you on developing leadership at your school, please visit his website at https://www.aidansevers.com/services and get in touch via the contact details that can be found there.

Monday, 23 September 2019

Book review: 'The Boy With The Butterfly Mind' by Victoria Williamson

Family politics are never easy. Especially not when you're a kid with ADHD.

Family politics are never easy. Especially not when you're a kid who is trying everything, including being absolutely perfect, to make things how they used to be.

When Jamie and Elin's parents get together, and Jamie has to move in with Elin, things do not look good. With step-siblings, American boyfriends, new schools, changes in medication and school bullies to contend with, things get (realistically) messy. In 'The Boy With The Butterfly Mind' Victoria Williamson turns her forensic but empathetic lens on life for children when their parents split up. Those who haven't experienced it will get a glimpse into the lives of those who have, and those readers whose parents have split will be quietly glad to see themselves represented in the pages of a book.

Williamson manages to convey the agony of having to live with all the complications of medical conditions and broken families with enough sensitive humour to keep the reader wondering how things will all resolve. Will Jamie and Elin ever learn to get along? Will therapy and medicine help the children through their confusion and anger? How does friendship figure in such a tense family situation? Through a sequence of immersive set pieces the story romps along, not always joyfully, but always full of heart, driven by the well-painted characters and the believable plot lines.

Joining Lisa Thompson's 'The Day I Was Erased' and Stewart Foster's 'Check Mates' and 'All The Things That Could Go Wrong', this book serves as an insight for children and adult readers alike into the potential reasons behind the actions of children who at school get labelled as 'the naughty kid'. It's not often that other children are given reason to empathise with these children making this an important read for youngsters. Although fiction, this story serves as a powerful illustration of how acceptance and understanding can help others to manage the impact of their experiences and medical conditions.

Employing a dual narrative technique, with each chapter alternating between Jamie and Elin's point of view, 'The Boy With The Butterfly Mind', is a moving and compelling read. Capable of triggering an emotional response, Victoria Williamson's latest book is a brilliant follow-up to her debut novel 'Fox Girl And The White Gazelle', giving her fans something else equally as brilliant to get their teeth, and hearts, into.

https://discoverkelpies.co.uk/books/uncategorized/boy-with-the-butterfly-mind-2/

Family politics are never easy. Especially not when you're a kid who is trying everything, including being absolutely perfect, to make things how they used to be.

When Jamie and Elin's parents get together, and Jamie has to move in with Elin, things do not look good. With step-siblings, American boyfriends, new schools, changes in medication and school bullies to contend with, things get (realistically) messy. In 'The Boy With The Butterfly Mind' Victoria Williamson turns her forensic but empathetic lens on life for children when their parents split up. Those who haven't experienced it will get a glimpse into the lives of those who have, and those readers whose parents have split will be quietly glad to see themselves represented in the pages of a book.

Williamson manages to convey the agony of having to live with all the complications of medical conditions and broken families with enough sensitive humour to keep the reader wondering how things will all resolve. Will Jamie and Elin ever learn to get along? Will therapy and medicine help the children through their confusion and anger? How does friendship figure in such a tense family situation? Through a sequence of immersive set pieces the story romps along, not always joyfully, but always full of heart, driven by the well-painted characters and the believable plot lines.

Joining Lisa Thompson's 'The Day I Was Erased' and Stewart Foster's 'Check Mates' and 'All The Things That Could Go Wrong', this book serves as an insight for children and adult readers alike into the potential reasons behind the actions of children who at school get labelled as 'the naughty kid'. It's not often that other children are given reason to empathise with these children making this an important read for youngsters. Although fiction, this story serves as a powerful illustration of how acceptance and understanding can help others to manage the impact of their experiences and medical conditions.

Employing a dual narrative technique, with each chapter alternating between Jamie and Elin's point of view, 'The Boy With The Butterfly Mind', is a moving and compelling read. Capable of triggering an emotional response, Victoria Williamson's latest book is a brilliant follow-up to her debut novel 'Fox Girl And The White Gazelle', giving her fans something else equally as brilliant to get their teeth, and hearts, into.

https://discoverkelpies.co.uk/books/uncategorized/boy-with-the-butterfly-mind-2/

Friday, 20 September 2019

Extract From 'Guardians Of Magic' by Chris Riddell

An extract from Chris Riddell's latest book 'Guardians of Magic', the first book in the new 'The Cloud Horse Chronicles' series:

Chapter 1: The Runcible Spoon

Zam Zephyr woke early and climbed out of bed, careful not to disturb the other apprentice bakers of Bakery No. 9, who were still fast asleep around him.

It was the day before the Grand Duchess of Troutwine's Tea Ball and Zam was too excited and nervous to stay in bed. Today, they would bake for the tea ball tomorrow. All twelve bakeries in the city competed for the honour of making the most delicious treats for the ball. If anything went wrong again, after last year's disaster that put Bakery No. 9 at the bottom of the heap, Zam and his friends would be sent home in disgrace. The thought of his father's disappointed face was too much to bear. No, Zam thought. He would do anything he could to make sure that his baking was perfect.

In the corner of the attic dormitory, his best friend Langdale the goat boy was gently snoring. Beneath the flour-sack blanket, his hooves twitched as he dreamed of chasing blue butterflies through the summer pine forests of the Western Mountains. In the other corner, the two Shellac sisters clutched the comfort shawl they shared. In the cots in between, the gnome boys from the Grey Hills slept soundless and still, five to a blanket, their small grey-tufted heads just visible.

Looking out of the window, Zam could see the golden roofs of the palaces glittering in the early morning sunlight. He gazed up at a billowing cloud and made a wish: 'To bake the best gingerbread ever, he whispered. 'Cloud horse, cloud horse, far from view, make this wish of mine come true.'

Zam took his apron and cap from the hook and crept out of the attic, leaving his friends to their dreams.

Zam ran all the way down the stairs to the basement, opened the door to the flavour library, and stepped inside. This was his favourite place. He loved how precise, tidy and ordered everything was here. He smiled to himself. With everyone asleep upstairs, it was the perfect time of day to practise without any interruptions.

Shelves lined the basement walls from floor to vaulted ceiling. Looking up through the glass paving stone, Zam could see the shadows of feet walking overhead as people passed the doors of Bakery No. 9.

The shelves around him were stacked with jars of all shapes and sizes, each clearly labelled.

Zam selected the jars he needed, opening each one in turn and taking pinches of the powders they contained. Carefully, he placed the spices on little squares of baking parchment, which he folded neatly and placed in different pockets of his apron. Satisfied with his choices, Zam crossed the stone floor to a large chest of drawers set in an alcove. He opened a drawer labelled 'Index of Crusts' and selected one with crinkle-cut edges and memorized the baking instructions written in small lettering on the underside.

‘For a crumbly texture, short, intense mixing and slow bake in quiet oven ... Zam read. The memory of the calm, reassuring sound of the head baker's voice filled his head, as it always did when Zam read his recipes. 'For a more robust biscuit, easeful mixing with broad, generous spoon and a short, fierce bake in busy oven...

‘Broad, generous spoon,' Zam repeated to himself, returning the crinkle-cut crust to the drawer and closing it. He looked up and was about to select one of the wooden spoons, which hung from the hooks in the ceiling, when he trod on something. It was a large spoon he hadn't noticed lying on the flagstone floor.

'That is so careless,' Zam muttered, picking it up. The spoon was broad and long handled, carved from a single piece of wood, by the look of it. Zam turned it over. It was a slotted spoon, full of small holes, with three large ones near the base of the handle.

‘Easeful mixing with broad, generous spoon,' the head baker's voice sounded in Zam's head.

‘Perfect,' he said, wiping the spoon on his apron before slipping it into a pocket.

He selected a favourite battered old book from a shelf: The Art of Baking. “There you are," he said happily and climbed the back stairs to the kitchen.

An hour later, the other apprentice bakers had been woken by the six o'clock gong and were filing in, putting on their caps and rubbing the sleep from their eyes. Balthazar Boabab, the head baker of Bakery No. 9, followed them into the kitchen smiling.

'Good morning, apprentices!' he said cheerfully, peering over the top of his half-rim spectacles. “As you know, the twelve bakeries of Troutwine are baking for the Grand Duchess's Tea Ball tomorrow, and we all have our parts to play.W

The head baker smiled again, a little ruefully this time. 'Bakery No. 1 is doing the first tiers. Bakery No. 2 the second and third tiers. Fillings are being produced by bakeries No. 3, 4 and 5. While No. 6, 7 and 8 are baking pastry shells and meringues. - Bakeries No. 10 and 11 are fruitcake and turnovers, and Bakery No. 12 is making floating islands...' Balthazar Boabab took a deep breath. 'This means, once again, Bakery No. 9 is picking up the crumbs…'

The apprentice bakers began to mutter. It wasn't fair. They had tried so hard, but they weren't being given a chance.

'I know, I know ...' said the head baker. 'It's not ideal, but after last year's cake collapse and exploding-eclair incident, Bakery No. 9 has a lot to prove ...'

'But that wasn't our fault,' protested one of the gnomes.

'The last head baker didn't pay off the League of Rats, said Langdale the goat boy, stamping his hooves, "and they ruined everything…'

'Nothing was proved,' said Balthazar gently. 'I am head baker now, and things are different, aren't they?'

Zam and the other apprentices nodded. It was true. Bakery No. 9 had changed since Balthazar Boabab had taken over: no more bullying, tantrums or random punishments. The kitchen was a happy place, and everyone was respected and baking beautifully. It was just as well. A year ago, after the disaster of the last tea ball, Bakery No. 9 had almost been shut down and everyone sent home. If Balthazar hadn't joined them from the fashionable Bakery No. 12, the apprentices would have had no future. None of them wanted to let him down.

"But what about the rats?' asked Langdale anxiously.

‘Let me worry about them,' said the head baker, doing his best to sound cheerful. ‘After all, we have heard nothing from the rats since I arrived.

Meanwhile, you have baking to do. We will be making the crusts as well as gingerbread and some spun-sugar decorations. And, at the tea ball itself –

Balthazar cleared his throat; even he couldn't sound cheerful about the next bit – 'Bakery No. 9 will be doing the washing-up.

The apprentice bakers groaned.

‘Langdale and the Shellac sisters are on shortcrust pastry shells,' Balthazar instructed. 'Gnomes are on glazed piecrust. Zam, are you confident to bake the gingerbread and help me with the spun sugar?'

'Yes, head baker,' said Zam excitedly. “I've already been down in the flavour library ...

‘Baker's pet,' muttered Langdale.

Balthazar gave the goat boy a stern look. But before he could say anything, an unexpected sound silenced them all.

In the shop, the doorbell had rung, and now they could hear the scritch-scratch of claws on the floorboards.

'I smell a rat,' said Langdale.

Publishing 19th September 2019 | Hardback, £12.99 | Macmillan Children’s Books | ISBN 9781447277972

Chapter 1: The Runcible Spoon

Zam Zephyr woke early and climbed out of bed, careful not to disturb the other apprentice bakers of Bakery No. 9, who were still fast asleep around him.

It was the day before the Grand Duchess of Troutwine's Tea Ball and Zam was too excited and nervous to stay in bed. Today, they would bake for the tea ball tomorrow. All twelve bakeries in the city competed for the honour of making the most delicious treats for the ball. If anything went wrong again, after last year's disaster that put Bakery No. 9 at the bottom of the heap, Zam and his friends would be sent home in disgrace. The thought of his father's disappointed face was too much to bear. No, Zam thought. He would do anything he could to make sure that his baking was perfect.

In the corner of the attic dormitory, his best friend Langdale the goat boy was gently snoring. Beneath the flour-sack blanket, his hooves twitched as he dreamed of chasing blue butterflies through the summer pine forests of the Western Mountains. In the other corner, the two Shellac sisters clutched the comfort shawl they shared. In the cots in between, the gnome boys from the Grey Hills slept soundless and still, five to a blanket, their small grey-tufted heads just visible.

Looking out of the window, Zam could see the golden roofs of the palaces glittering in the early morning sunlight. He gazed up at a billowing cloud and made a wish: 'To bake the best gingerbread ever, he whispered. 'Cloud horse, cloud horse, far from view, make this wish of mine come true.'

Zam took his apron and cap from the hook and crept out of the attic, leaving his friends to their dreams.

Zam ran all the way down the stairs to the basement, opened the door to the flavour library, and stepped inside. This was his favourite place. He loved how precise, tidy and ordered everything was here. He smiled to himself. With everyone asleep upstairs, it was the perfect time of day to practise without any interruptions.

Shelves lined the basement walls from floor to vaulted ceiling. Looking up through the glass paving stone, Zam could see the shadows of feet walking overhead as people passed the doors of Bakery No. 9.

The shelves around him were stacked with jars of all shapes and sizes, each clearly labelled.

Zam selected the jars he needed, opening each one in turn and taking pinches of the powders they contained. Carefully, he placed the spices on little squares of baking parchment, which he folded neatly and placed in different pockets of his apron. Satisfied with his choices, Zam crossed the stone floor to a large chest of drawers set in an alcove. He opened a drawer labelled 'Index of Crusts' and selected one with crinkle-cut edges and memorized the baking instructions written in small lettering on the underside.

‘For a crumbly texture, short, intense mixing and slow bake in quiet oven ... Zam read. The memory of the calm, reassuring sound of the head baker's voice filled his head, as it always did when Zam read his recipes. 'For a more robust biscuit, easeful mixing with broad, generous spoon and a short, fierce bake in busy oven...

‘Broad, generous spoon,' Zam repeated to himself, returning the crinkle-cut crust to the drawer and closing it. He looked up and was about to select one of the wooden spoons, which hung from the hooks in the ceiling, when he trod on something. It was a large spoon he hadn't noticed lying on the flagstone floor.

'That is so careless,' Zam muttered, picking it up. The spoon was broad and long handled, carved from a single piece of wood, by the look of it. Zam turned it over. It was a slotted spoon, full of small holes, with three large ones near the base of the handle.

‘Easeful mixing with broad, generous spoon,' the head baker's voice sounded in Zam's head.

‘Perfect,' he said, wiping the spoon on his apron before slipping it into a pocket.

He selected a favourite battered old book from a shelf: The Art of Baking. “There you are," he said happily and climbed the back stairs to the kitchen.

An hour later, the other apprentice bakers had been woken by the six o'clock gong and were filing in, putting on their caps and rubbing the sleep from their eyes. Balthazar Boabab, the head baker of Bakery No. 9, followed them into the kitchen smiling.

'Good morning, apprentices!' he said cheerfully, peering over the top of his half-rim spectacles. “As you know, the twelve bakeries of Troutwine are baking for the Grand Duchess's Tea Ball tomorrow, and we all have our parts to play.W

The head baker smiled again, a little ruefully this time. 'Bakery No. 1 is doing the first tiers. Bakery No. 2 the second and third tiers. Fillings are being produced by bakeries No. 3, 4 and 5. While No. 6, 7 and 8 are baking pastry shells and meringues. - Bakeries No. 10 and 11 are fruitcake and turnovers, and Bakery No. 12 is making floating islands...' Balthazar Boabab took a deep breath. 'This means, once again, Bakery No. 9 is picking up the crumbs…'

The apprentice bakers began to mutter. It wasn't fair. They had tried so hard, but they weren't being given a chance.

'I know, I know ...' said the head baker. 'It's not ideal, but after last year's cake collapse and exploding-eclair incident, Bakery No. 9 has a lot to prove ...'

'But that wasn't our fault,' protested one of the gnomes.

'The last head baker didn't pay off the League of Rats, said Langdale the goat boy, stamping his hooves, "and they ruined everything…'

'Nothing was proved,' said Balthazar gently. 'I am head baker now, and things are different, aren't they?'

Zam and the other apprentices nodded. It was true. Bakery No. 9 had changed since Balthazar Boabab had taken over: no more bullying, tantrums or random punishments. The kitchen was a happy place, and everyone was respected and baking beautifully. It was just as well. A year ago, after the disaster of the last tea ball, Bakery No. 9 had almost been shut down and everyone sent home. If Balthazar hadn't joined them from the fashionable Bakery No. 12, the apprentices would have had no future. None of them wanted to let him down.

"But what about the rats?' asked Langdale anxiously.

‘Let me worry about them,' said the head baker, doing his best to sound cheerful. ‘After all, we have heard nothing from the rats since I arrived.

Meanwhile, you have baking to do. We will be making the crusts as well as gingerbread and some spun-sugar decorations. And, at the tea ball itself –

Balthazar cleared his throat; even he couldn't sound cheerful about the next bit – 'Bakery No. 9 will be doing the washing-up.

The apprentice bakers groaned.

‘Langdale and the Shellac sisters are on shortcrust pastry shells,' Balthazar instructed. 'Gnomes are on glazed piecrust. Zam, are you confident to bake the gingerbread and help me with the spun sugar?'

'Yes, head baker,' said Zam excitedly. “I've already been down in the flavour library ...

‘Baker's pet,' muttered Langdale.

Balthazar gave the goat boy a stern look. But before he could say anything, an unexpected sound silenced them all.

In the shop, the doorbell had rung, and now they could hear the scritch-scratch of claws on the floorboards.

'I smell a rat,' said Langdale.

Publishing 19th September 2019 | Hardback, £12.99 | Macmillan Children’s Books | ISBN 9781447277972

Labels:

book,

books,

children's books,

children's literature,

Chris Riddell,

reading

Monday, 16 September 2019

From the @TES Blog: 8 Routines For Teachers To Nail Before Half-Term

The Right Book for the Right Child (Guest Blog Post By Victoria Williamson)

I remember very clearly when my love affair with Jane Austen began.

It was the summer between fifth and sixth year of high school, when I was seventeen. I’d picked up Pride and Prejudice for the first time, but not because I actually wanted to read it. It was a stormy day despite it being July – too wet to walk up to the local library. It was back in the nineties before the internet, Kindle, and instant downloads were available. I wanted to curl up on the sofa to read, but I’d already been through every single book in the house. All that was left unread at the bottom of the bookshelf was a row of slightly faded classics belonging to my mother. I only picked the first one up as there was clearly a book-drought emergency going on, and I was desperate.

The reason I didn’t want to read it, was because I already knew it was going to be totally boring.

Well, I thought I knew it. I’d already ‘read’ the classics you see. When I was ten or eleven, thinking I was very clever, I branched out from my usual diet of fantasy and adventure books, and opened a copy of Bleak House by Charles Dickens. I can’t remember why now – it might have been another rainy day and another book emergency situation, but whatever the reason, I spent several miserable hours ploughing through page after page of unintelligible drivel about Lincoln’s Inn, Chancery, and a bunch of boring characters who said very dull things, before giving up in disgust.

I ‘knew’ from that point on that the classic novels teachers and book critics raved about were the literary equivalent of All Bran instead of Sugar Puffs, and I wasn’t interested in sampling any more.

I didn’t pick up another classic until that rainy day at seventeen, when I sped through Pride and Prejudice in a day and a night, emerging sleepy-eyed but breathless the next day to snatch Emma from the shelf before retreating back to my room to devour it. That summer, after running out of books by Austen, the Brontes and Mrs Gaskell, I tried Bleak House again. And what a difference! Where before I had waded thorough unintelligible passages without gaining any sense of what was going on, I now found an engaging, and often humorous tale of a tangled court system far beyond the ‘red tape’ that everyone was always complaining about in present-day newspapers. Where before I’d only seen dull characters who rambled on forever without saying anything at all, I discovered wit and caricature, and a cast of people I could empathise with.

That was when I realised that there wasn’t anything wrong with the literary classics – it was me who was the problem. Or rather, the mismatch between my reading ability when I was ten, and the understanding I had of the world at that age. I could read all of the words on the page, I just didn’t understand what half of them meant, and I thought the problem was with the story itself.

I was reminded of this little episode in my own reading history recently when I spent the summer in Zambia volunteering with the reading charity The Book Bus. One afternoon we were reading one-to-one with children in a community library, when I met Samuel. Samuel had a reading level far above the other children, and raced through the picture books and short stories they were struggling with. I asked him to pick a more complicated book to read with me for the last ten minutes, and after searching through the two bookshelves that comprised the small one-roomed library, he came back with a Ladybird book published in 1960, called ‘What to Look for in Autumn.’

He did his best with it. He could read all of the words – the descriptions of wood pigeons picking up the seeds to ‘fill their crops’, the harvesters – reapers, cutters and binders – putting the oats into ‘stooks’ and the information about various ‘mushrooms and fungi’, but he didn’t understand anything he was reading. Needless to say I looked out a more appropriate chapter book from the Book Bus’s well-stocked shelves for him to read the following week, but the incident reminded me of the importance of getting relevant books into children’s hands if we’re to ensure they’re not turned off by the reading experience.

This is a problem often encountered in schools when teachers are looking for books to recommend to children. A lot of the time we’re so focused on getting them to read ‘good’ books, the ones we enjoyed as children, or the ones deemed ‘worthy’ by critics, that we forget that reading ability isn’t the only thing we have to take into consideration. We have to match the child’s level of understanding to the texts that we’re recommending – or in the case of that Ladybird book, get rid of outdated books from our libraries entirely!

Children often find making the leap to more challenging books difficult, and comfort read the same books over and over again – sometimes even memorising them in anticipation of being asked to read aloud with an adult. If we’re to help them bridge this gap, we must make sure our recommendations are not only appropriate for their reading level, but match their understanding too, introducing new words and ideas gradually in ways that won’t put them off.

Samuel and I were both lucky – we loved reading enough that one bad experience wasn’t enough to put us off, but other children might not be so fortunate. Let’s ensure all children have the chance to discover the joy of reading, by getting the right books into the hands of the right child.

Samuel and I were both lucky – we loved reading enough that one bad experience wasn’t enough to put us off, but other children might not be so fortunate. Let’s ensure all children have the chance to discover the joy of reading, by getting the right books into the hands of the right child.

Victoria Williamson is the author of Fox Girl and the White Gazelle (click here for my review) and The Boy with the Butterfly Mind, both published by Floris Books.

It was the summer between fifth and sixth year of high school, when I was seventeen. I’d picked up Pride and Prejudice for the first time, but not because I actually wanted to read it. It was a stormy day despite it being July – too wet to walk up to the local library. It was back in the nineties before the internet, Kindle, and instant downloads were available. I wanted to curl up on the sofa to read, but I’d already been through every single book in the house. All that was left unread at the bottom of the bookshelf was a row of slightly faded classics belonging to my mother. I only picked the first one up as there was clearly a book-drought emergency going on, and I was desperate.

The reason I didn’t want to read it, was because I already knew it was going to be totally boring.

Well, I thought I knew it. I’d already ‘read’ the classics you see. When I was ten or eleven, thinking I was very clever, I branched out from my usual diet of fantasy and adventure books, and opened a copy of Bleak House by Charles Dickens. I can’t remember why now – it might have been another rainy day and another book emergency situation, but whatever the reason, I spent several miserable hours ploughing through page after page of unintelligible drivel about Lincoln’s Inn, Chancery, and a bunch of boring characters who said very dull things, before giving up in disgust.