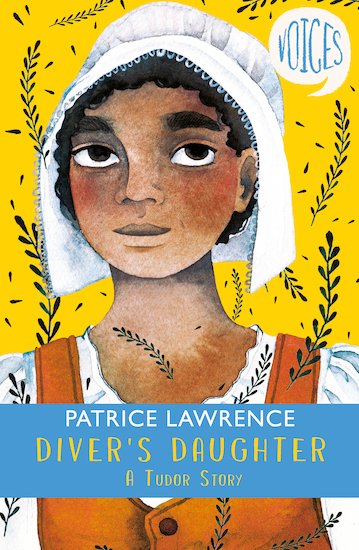

I've previously reviewed two other books from Scholastic's Voices series (here and here) and, after reading the first, I did not intend to stop there. 'Diver's Daughter' by Patrice Lawrence was next on the list.

Not exactly based on a true story, but involving one very real and pivotal character, this book is rooted in the true, often untold history of Black people in Tudor England. Having read the section in David Olusoga's Black and British that dealt with the Tudor period I had recently become more aware of the fact that there were hundreds of people from Africa or of African descent living in Britain in the 16th Century.

Eve is a Black Londoner, living, at the beginning of the story, a poor life in Southwark with her mother, a Mozambican by birth. Moving around, getting work where they can, they dream of a better life. Eve's mama is a diver and, faced with a chance to earn some real money in Portsmouth where the Mary Rose has sunk, they make a perilous journey in order to attempt to make their fortune, or at least in search of a better living. Along the way they are beset by illness, untrustworthy companions and ultimately, by their poor circumstances.

Upon arrival, things seem to look up for while, but not for long. The pair struggle to find work, and even the famous African diver Jacques Francis (historically significant not only as being lead salvage diver on the sunken Mary Rose, but also as the first Black person recorded to have given evidence in an English court) doesn't want to help them. They suffer the rejection of the townsfolk, betrayal by supposed friends before the racist viewpoints of the time lead to the kidnap of Eve's mama.

As well as being a thrilling, albeit sad, adventure, the book also evokes many other details of a time gone by - descriptions of living conditions, architecture and every day life as well as explanations of royal lineage and the tussle between religion and politics all ensure that young readers might even learn a thing or two as they read.

Providing, as I believe is the purpose of this range of stories, a way into Black British history for Key Stage 2-aged readers, this book is a great starting point for more learning around the ethnic diversity of Britain in Tudor times. Expertly written and exceedingly evocative, Patrice Lawrence's compelling narrative reveals, in a palatable way, the harsh realities of living in historical England as someone who is part of an ethnic minority group. A must for bookshelves at home, at school and in libraries.

Wednesday, 5 August 2020

Tuesday, 4 August 2020

Book Review: 'The Infinite' by Patience Agbabi

'The Infinite' by Patience Agbabi felt like a very unique read. What made it unique, I asked myself as a I read it - it was clear right from the beginning that this was something else.

Well, perhaps, it is the fact that you are plunged headlong into a world which at first, you do not understand. And there are layers to this world.

Perhaps the one layer is to do with the fact that Elle lives with her Nigerian grandmother - beautiful snippets of Nigerian culture are scattered throughout the story. Obviously some readers will understand and identify with this, but for this White British reader it was a great opportunity to learn more. I was, however, able to identify with Elle's grandmother's strong Christian faith - another thread that runs through the book.

The next layer to the world that the reader enters upon opening up 'The Infinite' is that Elle has some un-named additional needs. Given that the story is told from a first person perspective, this comes into play a lot. As such, characterisation is strong: the reader really gets to know Elle. We know she needs to sit under tables in certain situations; we know sometimes she spends days without speaking as she deals with trauma. And in this way, understanding of the world Elle inhabits grows as progress is made through the book. It's not only the protagonist who is characterised well - Elle's first person narrative is open and honest - she speaks the truth about the people she encounters in the story meaning that the reader builds up a great picture of the diverse cast of Elle's friends and acquaintances.

And then there is the fact that Elle is a Leapling - one who is born on the 29th of February - who has The Gift - specifically, the gift of being able to time travel. It takes some time to adjust to what is actually a very well-thought-through concept of time travel, and it is this that will draw any curious reader further into this book. Essentially, this is crime fiction, but very much complicated by the fact that crime can happen across time if perpetrated by others with The Gift. The story concludes satisfyingly and logically - a testament to the fact that the parameters of Agbabi's concept of time travel are very well-communicated throughout the book.

'The Infinite' is a really inventive, imaginative and innovative book - I've certainly never read anything quite like it. Highly recommended.

Well, perhaps, it is the fact that you are plunged headlong into a world which at first, you do not understand. And there are layers to this world.

Perhaps the one layer is to do with the fact that Elle lives with her Nigerian grandmother - beautiful snippets of Nigerian culture are scattered throughout the story. Obviously some readers will understand and identify with this, but for this White British reader it was a great opportunity to learn more. I was, however, able to identify with Elle's grandmother's strong Christian faith - another thread that runs through the book.

The next layer to the world that the reader enters upon opening up 'The Infinite' is that Elle has some un-named additional needs. Given that the story is told from a first person perspective, this comes into play a lot. As such, characterisation is strong: the reader really gets to know Elle. We know she needs to sit under tables in certain situations; we know sometimes she spends days without speaking as she deals with trauma. And in this way, understanding of the world Elle inhabits grows as progress is made through the book. It's not only the protagonist who is characterised well - Elle's first person narrative is open and honest - she speaks the truth about the people she encounters in the story meaning that the reader builds up a great picture of the diverse cast of Elle's friends and acquaintances.

And then there is the fact that Elle is a Leapling - one who is born on the 29th of February - who has The Gift - specifically, the gift of being able to time travel. It takes some time to adjust to what is actually a very well-thought-through concept of time travel, and it is this that will draw any curious reader further into this book. Essentially, this is crime fiction, but very much complicated by the fact that crime can happen across time if perpetrated by others with The Gift. The story concludes satisfyingly and logically - a testament to the fact that the parameters of Agbabi's concept of time travel are very well-communicated throughout the book.

'The Infinite' is a really inventive, imaginative and innovative book - I've certainly never read anything quite like it. Highly recommended.

Sunday, 26 July 2020

Book Review: 'Spaghetti Hunters' by Morag Hood

Writing children's picture books that are loved by both adults and children can't be easy. But there is one avenue, open only to the most skillful of writers and illustrators, which, if nailed, is a sure-fire way to appeal to both parties in the pre-bedtime reading session: surreal comedy.

Morag Hood combines her bold illustrations with limited wry text to hilarious effect. From the zany story line (a duck has lost his spaghetti and is aided in its attempted retrieval by a character called Tiny Horse, who is, indeed, a tiny horse) to the seemingly-incidental props (duck lives in a teapot, Tiny Horse's lecture on the finding of 'the trickiest of all pastas', the peanut butter which forms part of their hunting equipment) every word, every image has been selected for humourous purposes. 'Spaghetti Hunters' is (age appropriate Reeves and Mortimer-style frivolity in picture book form. When this is featured on Cbeebies Bedtime Stories it would only be right for Noel Fielding, or someone of that ilk, to read it.

'Spaghetti Hunters' is a celebration of more traditional pastimes - reading books, going fishing and home cooking are all on the table here - and is a gentle challenge to children (and perhaps some adults) as to where our food comes from. And whereas many books for children of this age focus on a harmonious, friendly relationship, Duck and Tiny Horse's friendship is a little more strained. During the story Duck, although clearly agitated (the eyebrows give it away, and the mental image of a duck trying to stomp off) by Tiny Horse's seemingly-pointless antics, demonstrates the patience needed when your friend has different ideas to you.

Morag Hood more than understands the necessity for images to mesh seamlessly with the words - the greatest outcome of this in this book is that the characters are so well portrayed - you know Duck and you know Tiny Horse within a few pages and, by the end, despite Tiny Horse's misplaced enthusiasm and single-mindedness, you feel like they are your friends. The rich but uncluttered illustrations make re-reading an extra pleasure - why do they need matching hats for spaghetti hunting?!

A perfect launch pad for some back catalogue delving (I'd heartily recommend 'The Steves'), 'Spaghetti Hunters' is a great bit of fun and has been a hit in my household with children across the primary age range. Books that are supposed to be funny are easily come by, but books which genuinely are don't come along all that often: Morag Hood's quirky style shines again in this one - a necessary addition to your child's bookshelf, for sure.

Morag Hood combines her bold illustrations with limited wry text to hilarious effect. From the zany story line (a duck has lost his spaghetti and is aided in its attempted retrieval by a character called Tiny Horse, who is, indeed, a tiny horse) to the seemingly-incidental props (duck lives in a teapot, Tiny Horse's lecture on the finding of 'the trickiest of all pastas', the peanut butter which forms part of their hunting equipment) every word, every image has been selected for humourous purposes. 'Spaghetti Hunters' is (age appropriate Reeves and Mortimer-style frivolity in picture book form. When this is featured on Cbeebies Bedtime Stories it would only be right for Noel Fielding, or someone of that ilk, to read it.

'Spaghetti Hunters' is a celebration of more traditional pastimes - reading books, going fishing and home cooking are all on the table here - and is a gentle challenge to children (and perhaps some adults) as to where our food comes from. And whereas many books for children of this age focus on a harmonious, friendly relationship, Duck and Tiny Horse's friendship is a little more strained. During the story Duck, although clearly agitated (the eyebrows give it away, and the mental image of a duck trying to stomp off) by Tiny Horse's seemingly-pointless antics, demonstrates the patience needed when your friend has different ideas to you.

Morag Hood more than understands the necessity for images to mesh seamlessly with the words - the greatest outcome of this in this book is that the characters are so well portrayed - you know Duck and you know Tiny Horse within a few pages and, by the end, despite Tiny Horse's misplaced enthusiasm and single-mindedness, you feel like they are your friends. The rich but uncluttered illustrations make re-reading an extra pleasure - why do they need matching hats for spaghetti hunting?!

A perfect launch pad for some back catalogue delving (I'd heartily recommend 'The Steves'), 'Spaghetti Hunters' is a great bit of fun and has been a hit in my household with children across the primary age range. Books that are supposed to be funny are easily come by, but books which genuinely are don't come along all that often: Morag Hood's quirky style shines again in this one - a necessary addition to your child's bookshelf, for sure.

Labels:

Book review,

book reviews,

children's books,

picture book

Friday, 17 July 2020

Guest Blog Post: Storyboarding With Children by Bethan Woollvin

After playing with traditional tales and creating my own twisted versions, including Little Red, Rapunzel and Hansel & Gretel, I decided I was up for a new challenge. Wanting to stay in the fairytale realm, I began channeling my love for folklore and traditional tales to write my own, more contemporary tale.

Anchored in a medieval era, I Can Catch a Monster follows a little girl who desperately wants to go monster-hunting with her brothers, but is told she is far too small! Exploring the kingdom anyway, she goes on a quest of her own to catch herself a monster, meeting some unlikely friends along the way!

Though I Can Catch a Monster is a step in a slightly different direction for my books, the idea unfolded in the same way that most of my books do - through pictures. I’ve always considered myself to be more confident as an artist than as a writer, and this is really due to how I think. I’m an incredibly visual person, so all of the book ideas I create, I do so nearly entirely in pictures to begin with. After some interesting research into mythical creatures, folktales and medieval lore, I quickly jumped in to sketching my ideas across a storyboard. This helps me to quickly map out the story in small, rough drawings, helping me to tell as much of the story as possible in pictures as possible. Words come much later in my process, and I usually use them to fill in any gaps in my story.

When I visit schools for author events, one of the first things I admit to children is that I find writing really difficult at times. I share my more picture-based method of story creation, and remind them that there’s no right or wrong way to create a story. My aim is always to encourage children (or anyone really!) to have more fun when creating stories. Mirroring my exact process of creating new story ideas, we work on a wordless story activity together. I usually focus this activity on a theme such as - ‘Create your own twisted fairytale’. I ask them to draw their story across a storyboard without any words. I encourage them to think about their characters, the environment and how they might progress their story over several panels of the storyboard.

For those who find writing particularly difficult, this activity really lifts the burden of writing. I’ve noticed with this activity, that it allows children to be more imaginative with their characters, environments and overall story plots. Sometimes children even add in words after they’ve finished their storyboarding, using more complex storytelling techniques such as dialogue and humour! But most importantly they have fun creating their own stories, and will feel more confident when it comes to the next story they create.

To celebrate the publication of I Can Catch a Monster, I’ve adapted a version of this very activity which you can do at home or in the classroom. I hope you find this inspiring, and keep on creating exciting stories! Click here to download Bethan's printable storyboarding activity!

Labels:

blog tour,

book,

books,

children's books,

children's literature

Friday, 19 June 2020

Back to School: Recovery or Catch Up?

Recovery.

We’ve been hearing a lot of talk about recovery with regards to the curriculum we teach when schools can eventually reopen to all children.

But the question must be asked, what are we trying to recover?

Are we trying to re-cover past material to ensure that it is secure? Are we trying to recover normality and perhaps just try to ignore this blip? Are we trying to help staff and children to recover mentally from the upheaval - similar to how a hospital patient might need to recover? Are we talking of something akin to roadside recovery where we fix a problem and send them on their way, give them a tow to get them to a destination or just give them a jump start?

Maybe we need to attempt to do all of these and more.

But the recent talk of ‘catch up’ does not help us to do any of the above.

When we normally think of catch up we think of small groups of children taking part in an intensive burst of input over a short amount of time - indeed, research shows that this is exactly how catch up interventions should be run so that they have maximum impact.

Can this be replicated for whole classes of children, some of whom will have been doing very little at home, others of whom may have followed all the home learning set and really prospered from that? We certainly need, as ever, an individualised, responsive approach for each child, but it is fairly certain that when we are all back in school we will be ‘behind’ where we normally would be, even if it means everyone is equally behind.

It would be foolish to think that by the end of the first term we will have caught up and will be able to continue as we were back in February and March. To believe this surely puts us on very shaky ground. Any kind of intensive approach to recovery is almost certain to negative repercussions, not least where children’s well-being is concerned - and that of staff, for that matter.

Year after year we hear stories from teachers escaping toxic schools and even leaving the profession who speak out on the hothousing, cramming, cheating, off-rolling, flattening the grass, and other morally bankrupt practices that go on in schools in the name of ‘getting good results’.

Well, back to my question: what are we trying to recover? How do we define ‘good results’? What result are we wanting from that first term back? That second term back? That third term?

How long are we willing to give this? We don’t know how long this will impact learning for - we’ve never had a period this long without children learning in classrooms. Perhaps it will barely leave a mark academically, perhaps the effects of it will be with us for years? Maybe we are overstating the potential impact on mental health and once we are back everyone will just be happy to be there, but maybe it will effect some of us for a good while yet.

What’s for sure, at least in my mind, is that we need a slow, blended approach to recovery. We must focus on the academic but we must not neglect everything else - bear in mind that phrase ‘the whole child’ and extend that to ‘the whole person’ so that it takes in all the people who will be working in schools when we can finally open properly to all.

We can not revert back to a system cowed by accountability - arranged around statutory assessment. Maybe they will scrap SATS this year, or edit the content that children will be tested on. Then again, maybe they won’t. Either way, schools - leaders and teachers - need to be brave enough to stand up for what is right for their children.

Ideally, we’d have an education department who, instead of telling us that modelling and feedback are the ideal way to teach, were willing to consult the profession in order to create a system-wide interim framework. A slimmed-down curriculum outlining the essentials and cutting some of the extraneous stuff from the Maths and English curriculum. Many schools are doing this piece of work so it would make sense if we were all singing off the same hymn sheet. If this was provided by the DfE then any statutory tests could be adapted accordingly - but this is the bluest of blue sky thinking.

And in suggesting that we limit the core subject curricula, I am certainly not suggesting that the whole curriculum is narrowed. Children will need the depth and breadth more than ever. We mustn’t let all the gained ground in terms of the wider curriculum be lost. We need the arts - I surely don’t even need to remind of the mental health benefits of partaking in creative endeavours. History and Geography learning is equally as valid (especially as they are the most interesting and captivating parts of the curriculum - fact): these must not fall victim to a curriculum narrowing which focuses solely on getting to children to ‘where they should’ be in Maths and English.

Who is to say, in 2020/2021, Post-Covid19, where a child ‘should be’? Perhaps we need to define this, or perhaps it’s not something we can even put our finger on.

I’m sure that if Lord Adonis read this I’d run the risk of becoming another of his apologists for failure, but that’s not what I am. What I am is an optimistic realist who wants the best for the children returning to our schools and the staff teaching them. What I am is someone who has observed the UK education system over a number of years and have seen schools who really run the risk of falling for rhetoric and accountability that leads to practice which does not best serve their key stakeholders. What I am is someone who is committed to getting all children back to school, back to work even, as quickly as is safely possible. I am a leader who is committed to the highest of standards but who won’t take shortcuts to get there.

When it comes to success(ful recovery) there are no shortcuts.

Some important other reads:

http://daisi.education/learning-loss/ - Learning Loss from Daisi Education (Data, Analysis & Insight for School Improvement)

https://www.adoptionuk.org/blog/the-myth-of-catching-up-after-covid-19 - The myth of ‘catching up’ after Covid-19 by Rebecca Brooks of Adoption UK

https://researchschool.org.uk/unity/news/canaries-down-the-coalmine-what-next-for-pupil-premium-strategy/ - Canaries Down the Coalmine: What Next for Pupil Premium Strategy? by Marc Rowland - Unity Pupil Premium Adviser

We’ve been hearing a lot of talk about recovery with regards to the curriculum we teach when schools can eventually reopen to all children.

But the question must be asked, what are we trying to recover?

Are we trying to re-cover past material to ensure that it is secure? Are we trying to recover normality and perhaps just try to ignore this blip? Are we trying to help staff and children to recover mentally from the upheaval - similar to how a hospital patient might need to recover? Are we talking of something akin to roadside recovery where we fix a problem and send them on their way, give them a tow to get them to a destination or just give them a jump start?

Maybe we need to attempt to do all of these and more.

But the recent talk of ‘catch up’ does not help us to do any of the above.

When we normally think of catch up we think of small groups of children taking part in an intensive burst of input over a short amount of time - indeed, research shows that this is exactly how catch up interventions should be run so that they have maximum impact.

Can this be replicated for whole classes of children, some of whom will have been doing very little at home, others of whom may have followed all the home learning set and really prospered from that? We certainly need, as ever, an individualised, responsive approach for each child, but it is fairly certain that when we are all back in school we will be ‘behind’ where we normally would be, even if it means everyone is equally behind.

It would be foolish to think that by the end of the first term we will have caught up and will be able to continue as we were back in February and March. To believe this surely puts us on very shaky ground. Any kind of intensive approach to recovery is almost certain to negative repercussions, not least where children’s well-being is concerned - and that of staff, for that matter.

Year after year we hear stories from teachers escaping toxic schools and even leaving the profession who speak out on the hothousing, cramming, cheating, off-rolling, flattening the grass, and other morally bankrupt practices that go on in schools in the name of ‘getting good results’.

Well, back to my question: what are we trying to recover? How do we define ‘good results’? What result are we wanting from that first term back? That second term back? That third term?

How long are we willing to give this? We don’t know how long this will impact learning for - we’ve never had a period this long without children learning in classrooms. Perhaps it will barely leave a mark academically, perhaps the effects of it will be with us for years? Maybe we are overstating the potential impact on mental health and once we are back everyone will just be happy to be there, but maybe it will effect some of us for a good while yet.

What’s for sure, at least in my mind, is that we need a slow, blended approach to recovery. We must focus on the academic but we must not neglect everything else - bear in mind that phrase ‘the whole child’ and extend that to ‘the whole person’ so that it takes in all the people who will be working in schools when we can finally open properly to all.

We can not revert back to a system cowed by accountability - arranged around statutory assessment. Maybe they will scrap SATS this year, or edit the content that children will be tested on. Then again, maybe they won’t. Either way, schools - leaders and teachers - need to be brave enough to stand up for what is right for their children.

Ideally, we’d have an education department who, instead of telling us that modelling and feedback are the ideal way to teach, were willing to consult the profession in order to create a system-wide interim framework. A slimmed-down curriculum outlining the essentials and cutting some of the extraneous stuff from the Maths and English curriculum. Many schools are doing this piece of work so it would make sense if we were all singing off the same hymn sheet. If this was provided by the DfE then any statutory tests could be adapted accordingly - but this is the bluest of blue sky thinking.

And in suggesting that we limit the core subject curricula, I am certainly not suggesting that the whole curriculum is narrowed. Children will need the depth and breadth more than ever. We mustn’t let all the gained ground in terms of the wider curriculum be lost. We need the arts - I surely don’t even need to remind of the mental health benefits of partaking in creative endeavours. History and Geography learning is equally as valid (especially as they are the most interesting and captivating parts of the curriculum - fact): these must not fall victim to a curriculum narrowing which focuses solely on getting to children to ‘where they should’ be in Maths and English.

Who is to say, in 2020/2021, Post-Covid19, where a child ‘should be’? Perhaps we need to define this, or perhaps it’s not something we can even put our finger on.

I’m sure that if Lord Adonis read this I’d run the risk of becoming another of his apologists for failure, but that’s not what I am. What I am is an optimistic realist who wants the best for the children returning to our schools and the staff teaching them. What I am is someone who has observed the UK education system over a number of years and have seen schools who really run the risk of falling for rhetoric and accountability that leads to practice which does not best serve their key stakeholders. What I am is someone who is committed to getting all children back to school, back to work even, as quickly as is safely possible. I am a leader who is committed to the highest of standards but who won’t take shortcuts to get there.

When it comes to success(ful recovery) there are no shortcuts.

Some important other reads:

http://daisi.education/learning-loss/ - Learning Loss from Daisi Education (Data, Analysis & Insight for School Improvement)

https://www.adoptionuk.org/blog/the-myth-of-catching-up-after-covid-19 - The myth of ‘catching up’ after Covid-19 by Rebecca Brooks of Adoption UK

https://researchschool.org.uk/unity/news/canaries-down-the-coalmine-what-next-for-pupil-premium-strategy/ - Canaries Down the Coalmine: What Next for Pupil Premium Strategy? by Marc Rowland - Unity Pupil Premium Adviser

Monday, 8 June 2020

Decolonising and Diversifying the Primary History Curriculum: A Journey (Part 1)

Before you read this, please consume Jeffrey Boakye's 'The long, insidious, shadows of colonialism': https://bigeducation.org/learning-from-lockdown/lfl-content/the-long-insidious-shadows-of-colonialism/

And, if you've got even longer, seek out both Akala's 'Natives' and Reni Eddo-Lodge's 'Why I'm No Longer Talking To White People About Race' who both have a little longer to convince you of why it is necessary that we decolonise the curriculum.

If you're still here, and it is OK not to be because the above articles are far more important than my own, I'd like to mull over what we might do to decolonise and diversify the primary curriculum. Writing this way is my way of thinking things through, but it may help some readers on their own journey. It may be that I get loads wrong - in this case I hope I am told I am wrong by those who know better. Hopefully, in the very least, it can be a conversation starter that moves us all on in our thinking, understanding and actions.

For the purposes of this blog post, I have set a starting point for myself of analysing the subject of History, and more specifically, British History.

In the above article Boakye says: "In education, manifestations of structural racism are both dramatic and visible. We can list them: The pervasive whiteness of our curriculum. The lack of criticality towards Britain’s colonial past. The lack of diversity in texts, narratives and voices."

What I want to consider is how we can begin to make meaningful changes to the curriculum we teach. Rewriting a whole curriculum is something that takes time and collective decisions. So, for practicality, first of all I ask, is it possible to adapt our current curriculum in order to better represent the history of BAME people and to begin to deconstruct systemic racism?

In his book 'Black and British', David Olusoga writes: "Black history is too often regarded as a segregated, ghettoized narrative that runs in its own shallow channel alongside the mainstream, only very occasionally becoming a tributary into that broader narrative. But black British history is not an optional extra. Nor is it a bolt-on addition to mainstream British history deployed only occasionally in order to add – literally – a splash of colour to favoured epochs of the national story. It is an integral and essential aspect of mainstream British history. Britain’s interactions with Africa, the role of black people within British history and the history of the empire are too significant to be marginalized, brushed under the carpet or corralled into some historical annexe."

Firstly, if we are considering adapting the curriculum, we really must be serious about avoiding the pitfalls that Olusoga outlines above:

And, if you've got even longer, seek out both Akala's 'Natives' and Reni Eddo-Lodge's 'Why I'm No Longer Talking To White People About Race' who both have a little longer to convince you of why it is necessary that we decolonise the curriculum.

If you're still here, and it is OK not to be because the above articles are far more important than my own, I'd like to mull over what we might do to decolonise and diversify the primary curriculum. Writing this way is my way of thinking things through, but it may help some readers on their own journey. It may be that I get loads wrong - in this case I hope I am told I am wrong by those who know better. Hopefully, in the very least, it can be a conversation starter that moves us all on in our thinking, understanding and actions.

For the purposes of this blog post, I have set a starting point for myself of analysing the subject of History, and more specifically, British History.

In the above article Boakye says: "In education, manifestations of structural racism are both dramatic and visible. We can list them: The pervasive whiteness of our curriculum. The lack of criticality towards Britain’s colonial past. The lack of diversity in texts, narratives and voices."

What I want to consider is how we can begin to make meaningful changes to the curriculum we teach. Rewriting a whole curriculum is something that takes time and collective decisions. So, for practicality, first of all I ask, is it possible to adapt our current curriculum in order to better represent the history of BAME people and to begin to deconstruct systemic racism?

In his book 'Black and British', David Olusoga writes: "Black history is too often regarded as a segregated, ghettoized narrative that runs in its own shallow channel alongside the mainstream, only very occasionally becoming a tributary into that broader narrative. But black British history is not an optional extra. Nor is it a bolt-on addition to mainstream British history deployed only occasionally in order to add – literally – a splash of colour to favoured epochs of the national story. It is an integral and essential aspect of mainstream British history. Britain’s interactions with Africa, the role of black people within British history and the history of the empire are too significant to be marginalized, brushed under the carpet or corralled into some historical annexe."

Firstly, if we are considering adapting the curriculum, we really must be serious about avoiding the pitfalls that Olusoga outlines above:

- Black history cannot be optional - it must be insisted on, part of the written, set curriculum, and shouldn't be left to the whims and desires and expertise, or lack thereof, of individual teachers - it almost needs to be set in stone. Why does it have to be there? Look at the last sentence of the Olusoga quote - that's the truth.

- Black history should not be seen as a bolt-on - it should not just be 1 lesson in 12 which, for example, highlights a famous black person from history. This will be seen, whether consciously or sub-consciously, as paying lip service to teaching black history. Students under this curriculum will know that it means that it doesn't matter as much as the other 11 lessons.

- Black history can, and should be, black British history - there are more easily-accessible resources out there to teach about the American Civil Rights Movement, Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, but we need to to do better than this. Actually, there would be no black American history if it was not for black British history - we, and other European countries, were the colonisers. The Atlantic slave trade should not be taught as disconnected from the ones who made it all happen - the British, the Spanish, the Portuguese, the French, the Dutch and the Danish. Teaching slavery as something that only happened in America in the cotton fields is dishonest.

Secondly, we must ask if teaching Black history is the same as truly decolonising the curriculum. Actually, if you take Boakye's quote from above, there is a separation between making the curriculum less 'white' and being more critical of Britain's colonial past.

Simply teaching about Mary Seacole, self-funded nurse in the Crimean War, without exploring her parentage (Scottish soldier father who was stationed by the British empire in Jamaica, Jamaican free-woman mother), and how Jamaica came to be peopled by those of African descent, may well be teaching some aspects of black history, but it is not decolonising the curriculum, or attempting at all to deconstruct systemic racism. It is hiding away inconvenient truths about Britain's not-so-great past. Truths that make us feel uncomfortable - that's if we even bother to question and find out about them in the first place.

To us white teachers, it might actually be quite scary to begin to ask the question Why are there black Britons? After all, it all sounds a bit racist to be even be focusing on the colour of their skin, or their ethnicity. It even feels sort of go-back-where-you-came-from - and most of us don't want to be racist at all.

Olusoga recounts how Stuart Hall, British-Jamaican sociologist, "explained to his British readers that the immigrants ‘are here because you were there’". If we pretend to be colour-blind then we ignore too much. He need to see ethnicity in our curriculum, and we need to interrogate and explain how the history of a black British person is deeply connected to any other aspect British history, particularly colonialism, because it inevitably will be. In carrying out this kind of investigation, both at planning stage as teachers, and with the children during lessons, we will begin to decolonise the curriculum.

But in doing that, we will only begin to decolonise the curriculum. The next step would be to call into question the actions of the British empire. I don't think I'm too naive to think that most children, when exposed to the truths of the British empire's modus operandi the world over, will quite quickly identify the injustices, cruelty and immorality.

However, children will not have the chance to identify the above if teachers do not present it to them. And teachers who have also grown up within the British education system have also fallen prey to its whitewashed curriculum and scarce mentioning of the actions of the empire and its colonists, slave traders and apologists. We teachers must educate ourselves. It won't be enough to download a powerpoint from TES about Harriet Tubman and teach through that one afternoon. We have to know so much more. In order to educate or children we must educate ourselves - I can guarantee that there are very few of us who actually know enough history to really begin to make amends - myself included.

My current action - and I believe sharing our actions is a good thing to do, even if it might seem self-centred - is to read the aforementioned David Olusoga book. Now that I am convinced of the need to see colour, and that the curriculum does need a major renovation, I know I must read incessantly to begin to learn everything that my education has so far deprived me of. As I've read I have already identified lots of interesting case studies which can be brought into the current units of work as set out by the National Curriculum. I have noted areas of the History curriculum that most schools cover which should take in significant portions of history which, if taught and critiqued, would be a good step towards providing a decolonised primary curriculum. I already have some ideas forming of how the curriculum at my school, which is by no means devoid of BAME history, can be vastly improved. I also benefit from standing at a point in time where I am currently writing unit overviews which outline the content of each session within the sequence so find myself well placed to really set things in place which ensure a better curriculum for the future.

At the outset I asked is it possible to adapt our current curriculum in order to better represent the history of BAME people and to begin to deconstruct systemic racism? I'm not sure that in the above ramblings I have actually answered that question. Instead I think I may have extracted from the writings of more knowledgeable people than I some principles that might help me as I continue on my journey to having a decolonised and diversified primary curriculum. It remains my quest to continue to learn, to think and to create in order to come closer to answering that question.

And if the answer to the questions ends up being a no? Well, then I suppose a complete rewrite is in order.

I would love to hear from any readers who have been prompted by any thoughts or questions about the primary curriculum during the reading of this, or indeed during the last few days. I know that my own musings will be hugely enhanced by some collaboration and discussion, and as mentioned at the start, I am open to criticism (although would request, if I may, that it remains constructive and is conducted in a respectful manner). Crucially, I acknowledge the fact that as a white British male, my curriculum design, even after reading books by people who know what they're talking about, might still not cut the mustard - I will need to listen to the voices of those who are most negatively affected by the current colonised curriculum. Please do speak and join with me in this journey.

Next I will most likely tackle the question if it is possible to adapt the current curriculum, in what ways would we go about doing that? in which I will hopefully be able to share some specific examples pertaining to specific units within the primary history curriculum of how the curriculum could be decolonised and diversified. In doing so I am sure that I will be able to share a great many resources that are already in existence, as well as perhaps some of my own ideas.

Wednesday, 3 June 2020

#BlackLivesMatter - A Pledge

I had a rough night last night - couldn't sleep properly. Dreams were haunted. And I knew it would be so. I went to bed with thoughts of Bunce Island (I started reading Black and British by David Olusoga), Cyntoia Brown (we watched the Netflix documentary which I've subsequently found out was not approved by her) and the lack of representative diversity in our SLT running around my head (this was the topic of conversation with my wife before we went to sleep). I was afraid to go to sleep because I knew it would be disturbed.

But even this reading of books is not enough, I know. I'm not sure exactly where the quote comes from, but this from Angela Davis is key: "In a racist society, it is not enough to be non-racist, we must be antiracist."

What does it look like for me to be antiracist? This is a big question, and one that I can't answer immediately. This list of ten things from BAMEed is a good starting point for me, and anyone finding themselves in a similar position:

But, if that's all I've got to be afraid of, then I'm priviliged. This privilege is something I am aware of already, but when I compare my fears to those of people who see George Floyd being murdered by police and know that it could happen to them because of the deep-seated racism that exists at a systemic level, I have to remind myself that I can cope with a rough night.

However, it is right that I should be disrupted - this should be my burden. As a white middle-class male I have benefited from the privilege that comes with that all my life and I know I've not done anywhere near enough to advocate for people who don't have that privilege.

When it comes to being an ally, I know that loving music of black origin isn't enough. As Clara Amfo said, "We black people get the feeling that people want our culture but they do not want us. In other words, you want my talent but you don't want me.". I do think I've learned from Hip Hop particularly a little of what life for black people is like as they experience the systemic racism around them but if I'm honest, I've still come away with a false overall impression of life as a black person being a pretty cool thing. I am ashamed to admit this, but it is important that I do.

When it comes to being an ally, I know that loving music of black origin isn't enough. As Clara Amfo said, "We black people get the feeling that people want our culture but they do not want us. In other words, you want my talent but you don't want me.". I do think I've learned from Hip Hop particularly a little of what life for black people is like as they experience the systemic racism around them but if I'm honest, I've still come away with a false overall impression of life as a black person being a pretty cool thing. I am ashamed to admit this, but it is important that I do.

In the last couple of years I have begun to try to educate myself by reading both 'Why I'm No Longer Talking To White People About Race- by Reni Eddo-Lodge and 'Natives' by Akala. I've been heartened to see that many have pointed towards these volumes, as well as others, as being a good starting point for white people who 'want to do something'. Education is the best starting point, as illustrator Dapo Adeola said:“You cannot enjoy the rhythm and ignore the blues”— BBC Radio 1 (@BBCR1) June 2, 2020

This is incredibly powerful from @claraamfo on the death of George Floyd, racism and its effect on her own mental health. pic.twitter.com/qxHrvKfn0e

It's because of my reading of the aforementioned books that when I watched this clip of George The Poet on Newsnight, that I already knew that the presenter was wrong in her question:“If you feel what I’m saying here then it’s down to you to seek answers, educate yourselves, READ, listen to Black people when they tell you “something’s off”, read the rooms you’re in when in professional gatherings if they’re colourless, ask yourself “why”?” https://t.co/VuGKv2UlKf— Aidan Severs (@thatboycanteach) June 3, 2020

I was pleased to see that many others appear to have finally taken up the responsibility to self-educate: Amazon's best seller list this morning featured 'Why I'm No Longer Talking To White People About Race' at number 1, as well as 'Me and White Supremacy' by Layla F Saad, Natives by Akala, 'How To Argue With A Racist by Adam Rutherford and other books by black authors, fiction and non-fiction.“But you're not putting Britain & America on the same footing? Our police aren't armed, they don't have guns, the legacy of slavery is not the same. It's not the same, is it?”— Nadine White (@Nadine_Writes) June 2, 2020

- @GeorgeThePoet explains why racism in the US & UK is the same on #Newsnight. pic.twitter.com/TcRBXh4Spl

The BAMEed network website has a really good booklist aimed at educating teachers, or anyone who is wanting to learn more about how systemic racism is: https://www.bameednetwork.com/books/Really glad to see some of the titles in Amazon’s current best sellers list.— Aidan Severs (@thatboycanteach) June 3, 2020

Perhaps people are finally waking up to what is going on in the world around them are deciding to do something about educating themselves about it.

Other booksellers are available. pic.twitter.com/TIzr1ixzio

But even this reading of books is not enough, I know. I'm not sure exactly where the quote comes from, but this from Angela Davis is key: "In a racist society, it is not enough to be non-racist, we must be antiracist."

What does it look like for me to be antiracist? This is a big question, and one that I can't answer immediately. This list of ten things from BAMEed is a good starting point for me, and anyone finding themselves in a similar position:

I feel like this advice; though a helpful start, might need to include a few more steps now.— Dr Muna Abdi #BlackLivesMatter (@Muna_Abdi_Phd) May 31, 2020

We need allies that don't simply advocate, but truly stand and walk in solidarity with us... and that means being an accomplice and co-conspirators if need be. pic.twitter.com/mKKiMPMo2u

The above document can be downloaded as a PDF here: https://www.bameednetwork.com/resources/

I think the important next step here is to recognise that being an ally, an advocate and an activist starts where one is already: in my home, with my daughters, with my friends and family, in my church, in my job as a school leader, and so on - this is reflected in points 4, 5 and 9. This will require an ever-shifting mindset; a constantly growing set of filters for thought processes: as I learn more about the history of racism and just how systemic it is, I will need to reflect this in how I think and how I make decisions.

The part of discovering and taking these next steps that is very nuanced is that which is outlined in point 8. I am not complaining about the difficulties that might be involved in trying to be an ally instead of a saviour - this is part of my role, and I would like to gladly take this on. I know as a school leader I have institutional power, even having 25k followers on Twitter means that I do - with this power comes responsibility but not ultimate responsibility - nowhere near. I must listen to the voices of black people, Asian people, and anyone who does not share my own ethnicity but I must not rely solely on them to tell me what to do - that is not their responsibility. There is enough information out there to guide me as to what my responsibility it, however I will always be ready to listen when they are ready to talk, always ready to learn when they are ready to teach.

I am aware that this blog post is probably riddled with my white privilege in ways which I cannot yet see. If you are reading this and you can see something that I can't - in the way I've phrased something, in omissions, in things I've written that don't mark me as a true ally, then I ask that you call me on it - this is how I will learn, this is how I will change.

Thank you for taking the time to read this - I pray it has not been an egocentric virtue signalling session, but a true pledge to do better.

I'd also love you to have a read of my wife's take on this matter over on her blog: White supremacy is in my blood; we need to get uncomfortable fast to defeat it

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)