Tom Palmer's latest run of war-themed stories continues with 'After The War: From Auschwitz to Ambleside' - a story focusing in on three Polish teenagers who are brought to the safety of the Lake District for recuperation after Europe is liberated in 1945.

The story follows Yossi and his friends Mordecai and Leo as they arrive on the Calgarth Estate beside Lake Windemere and begin to attempt, with the help of a multitude of kind heroes, to rebuild their shattered lives. As they gain in strength and trust they have to make decisions about what to do and where to go next. Yossi lives in hope that the Red Cross will find his father yet life inevitably must move on whilst the search continues.

In this heartwarming tale of true and beautiful friendship, Tom Palmer communicates to a young audience with crystal-clear clarity the atrocities and the fall-out of war. As seen before in his books, he doesn't avoid the harsh realities, nor does he glorify them or play them down. Instead, he says just the right amount for the intended readership - a real skill. And, given the publisher Barrington Stoke's mission to provide credible, yet easy-to-read books for less confident readers, it is remarkable that a book written in a more simplistic style than others in its category has emotional depth beyond that of its peers.

In fact, perhaps the low use of complex language is all a technique to help us to understand Yossi. Here is a teenager who speaks no English, yet finds himself in the middle of the English countryside. Here is a teenager whose life has been devastated and dominated by cruelty beyond words. The narration of the story only serves to help us to know and love the character as he finds the meaning to life once more, as he learns to express himself to those around him and as he finds and understands himself once more.

With lots of World War Two references, particularly to warplanes, and the trademark sport references (I was pleased to read Yossi's celebration of the bicycle), this is exactly what I wanted from a new Tom Palmer novel. A tale of hope, friendship and altruism that is all too relevant in the current times we are living through.

After the War: From Auschwitz to Ambleside will publish on 7 May 2020 in Barrington Stoke’s middle-grade Conkers series.

Monday, 23 March 2020

Wednesday, 18 March 2020

Why We Cancelled Our School Residential

Written before the announcement that schools will close to children other than those of key workers. I have also just heard that the council made the call to close the residential centre this afternoon, too.

And what if a child begins to display symptoms of COVID-19 in the middle of the night? I asked myself as I added to my risk assessment for our very imminent residential visit. I’d already imagined a scenario in which we didn’t have enough staff or children on the morning we were due to leave to make the visit viable.

At first the night time scenario seemed like the worst thing that could happen. But then I began to consider what would happen if a child or member of staff began to show symptoms during the day.

A member of staff would have to contact me, wherever I was: down a cave, climbing a gully, trekking though the Dales. Mobile phone reception isn’t exactly forthcoming out in the wilds of North Yorkshire.

I’d have to contact the school – with the same complications as above - who would then need to contact parents. Then what would happen? Would we ask parents to come and collect? Or should I ask the member of staff who had brought a car to take them home? But what if it was more than one child? Should I actually be taking the school minibus so that I could return poorly children to school as quickly as possible?

And what if it was members of staff who came down with something? Would we be left with insufficient ratios to really safeguard the children on an outward bound adventure holiday? Would we call on other staff from school to join us? But what if school had begun to experience staff absences? I didn’t even consider what might have to happen if I – the one who had spent endless hours planning the visit – got ill. Did anyone else know enough about the ins and outs of the residential to be able to run it in my absence?

So many questions. No encouraging answers. In my mind I came to the conclusion that if a child or adult developed a dry cough or a high temperature, I’d have to get them home as quickly as possible, followed swiftly by the rest of the children. If one child had it, then how many others might have been infected during the stay?

The evening after completing a risk assessment which had led me to believe that actually, this residential was quite a risk – one I was not happy to shoulder the burden of, the government upped the ante with their advice. The words ‘non-essential’ were used several times. Although I totally believe in the importance of such an experience for children living in the city, I was pretty sure it fell into the ‘non-essential’ category.

Sir, is the residential still on? I was asked by eager children the following morning. They were aware of the fragility of the chance of it going ahead. I had to give disappointingly non-committal answers – I didn’t want to cause undue upset. I was asked the same question by parents on the gate – some of whom wanted to know when they should start packing, others expressed their own concerns.

But I had found myself at a standstill. I thought I should cancel the trip, but that would risk a financial loss to the school. Should I wait for the venue to cancel, or should I go ahead? I spoke to the deputy of another school who were going to the same venue as us during the same week – he was in the same position.

I came clean with the manager of the venue: we were worried about the risks but didn’t want to lose the money – he was honest with me: they too were waiting for further guidance on school closure as to whether they were going to cancel forthcoming visits. I broached the subject of a postponement and requested potential dates for next academic year for the same cohort of children.

The happy ending to this story is that our trust’s early start date in August meant that we could find an early September slot that no other school would be able to take. All being well, the children will get to experience the great outdoors together for three days, albeit in six months’ time. We are all disappointed that although schools remain open, we won’t get our residential this year but safety comes first. A decision which puts the health and wellbeing of children and staff first is the best decision.

And what if a child begins to display symptoms of COVID-19 in the middle of the night? I asked myself as I added to my risk assessment for our very imminent residential visit. I’d already imagined a scenario in which we didn’t have enough staff or children on the morning we were due to leave to make the visit viable.

At first the night time scenario seemed like the worst thing that could happen. But then I began to consider what would happen if a child or member of staff began to show symptoms during the day.

A member of staff would have to contact me, wherever I was: down a cave, climbing a gully, trekking though the Dales. Mobile phone reception isn’t exactly forthcoming out in the wilds of North Yorkshire.

I’d have to contact the school – with the same complications as above - who would then need to contact parents. Then what would happen? Would we ask parents to come and collect? Or should I ask the member of staff who had brought a car to take them home? But what if it was more than one child? Should I actually be taking the school minibus so that I could return poorly children to school as quickly as possible?

And what if it was members of staff who came down with something? Would we be left with insufficient ratios to really safeguard the children on an outward bound adventure holiday? Would we call on other staff from school to join us? But what if school had begun to experience staff absences? I didn’t even consider what might have to happen if I – the one who had spent endless hours planning the visit – got ill. Did anyone else know enough about the ins and outs of the residential to be able to run it in my absence?

So many questions. No encouraging answers. In my mind I came to the conclusion that if a child or adult developed a dry cough or a high temperature, I’d have to get them home as quickly as possible, followed swiftly by the rest of the children. If one child had it, then how many others might have been infected during the stay?

The evening after completing a risk assessment which had led me to believe that actually, this residential was quite a risk – one I was not happy to shoulder the burden of, the government upped the ante with their advice. The words ‘non-essential’ were used several times. Although I totally believe in the importance of such an experience for children living in the city, I was pretty sure it fell into the ‘non-essential’ category.

Sir, is the residential still on? I was asked by eager children the following morning. They were aware of the fragility of the chance of it going ahead. I had to give disappointingly non-committal answers – I didn’t want to cause undue upset. I was asked the same question by parents on the gate – some of whom wanted to know when they should start packing, others expressed their own concerns.

But I had found myself at a standstill. I thought I should cancel the trip, but that would risk a financial loss to the school. Should I wait for the venue to cancel, or should I go ahead? I spoke to the deputy of another school who were going to the same venue as us during the same week – he was in the same position.

I came clean with the manager of the venue: we were worried about the risks but didn’t want to lose the money – he was honest with me: they too were waiting for further guidance on school closure as to whether they were going to cancel forthcoming visits. I broached the subject of a postponement and requested potential dates for next academic year for the same cohort of children.

The happy ending to this story is that our trust’s early start date in August meant that we could find an early September slot that no other school would be able to take. All being well, the children will get to experience the great outdoors together for three days, albeit in six months’ time. We are all disappointed that although schools remain open, we won’t get our residential this year but safety comes first. A decision which puts the health and wellbeing of children and staff first is the best decision.

Sunday, 15 March 2020

School Leadership: Hard or Complex?

Saturday, 15 February 2020

Getting Ready For The 2021 KS2 Reading Test (or 16 Reading Texts and SATs-Style Question Papers)

This blog post is now available at:

The question papers, texts and mark schemes are available at:

Labels:

comprehension,

ks2 sats,

reading,

reading comprehension,

reading lesson,

SATs,

SATs ks2

Monday, 10 February 2020

Friday, 17 January 2020

Guest Blog Post: The World of Masks by Anna Hoghton

Click here to read my review of The Mask of Aribella by Anna Hoghton.

In this guest blog post, author Anna Hoghton explains how she researched a key motif in her debut novel for children and shares some of her findings. A great read for anyone who has read the book, or wants to, and for teachers who want to encourage children to research information for their own stories:

In this guest blog post, author Anna Hoghton explains how she researched a key motif in her debut novel for children and shares some of her findings. A great read for anyone who has read the book, or wants to, and for teachers who want to encourage children to research information for their own stories:

Masks are clearly important in the world of my book – I mean, they’re in the title and on the front cover. Given that I was writing about Venice, I always knew I would use masks, it was just a question of how. What did I want masks to mean for my characters?

For inspiration, I investigated into how masks have been used throughout history. Masks have been used for centuries and the oldest mask ever found is from 7000 BC, though the art of mask making is likely to be even older than this. There are as many different styles of masks as there are different cultures and they’ve been used for everything: rituals, ceremonies, hunting, feasts, wars, in performances, theatres, fashion, art, sports, films, as well as for medical or protective reasons. Here are a few examples of how masks have been used by everyone from the ancient Greeks to Spiderman.

Ancient Greece

The iconic smiling comedy and frowning tragedy masks were used in ancient Greek theatre. Paired together, they showed the two extremes of the human psyche. Before this, Greeks also used masks in ceremonial rites and celebrations during the worship of Dionysus at Athens.

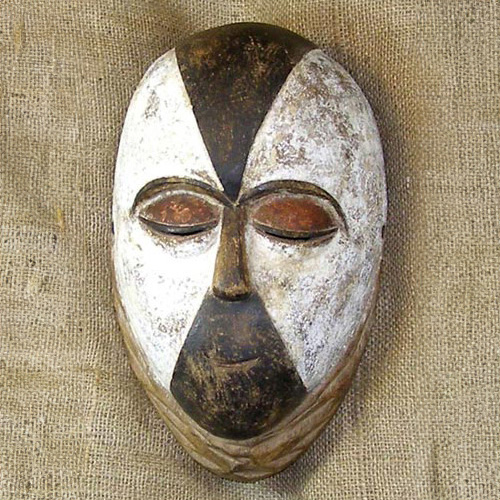

West Africa

In West Africa, masks are still used by some tribes (such as the Edo, Yoruba and Igbo cultures) as a way of communicating with ancestral spirits. These masks are skilfully made out of wood and often have human faces, though they are sometimes in the shapes of the animals. Some tribes believe that these animal masks allow them to communicate with the animal spirits of savannas and forests. Some tribes also use war masks with big eyes, angry expressions and bright colours to scare their enemies.

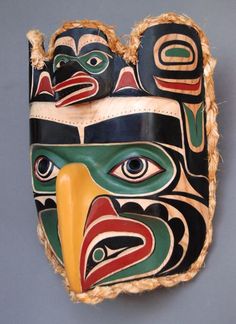

North America

In North America, the skilled woodworkers in coastal Inuit tribes make complex masks from wood, leather, bones and feathers. These masks are cleverly crafted, often with movable parts, and are very beautiful. Used in shamanic rituals, these masks represent the unity between the Inuit people, their ancestors and the animals that they hunt. When people are sick, the masks are also used to exorcize the evil spirits from them.

Oceania

In Oceania, where the culture of ancestral worship is very important, masks are made to represent ancestors. Sometimes these masks are enormous, even six metres high. They are also used to ward off evil spirits.

Latin America

Latin America

In Latin America, Ancient Aztecs used masks to cover the faces of their deceased. At first these funeral masks were made from leather, but later they were made out of copper and gold.

Venice (of course I had to mention this one)

In the Republic of Venice, the concealment of identity was part of daily activity and used to break down social boundaries. This was useful as it meant state inquisitors could find out truths without citizens knowing who they were. But masks also meant that people could get up to no good... Eventually the wearing of masks in daily life was banned except for during certain months of the year.

In the Republic of Venice, the concealment of identity was part of daily activity and used to break down social boundaries. This was useful as it meant state inquisitors could find out truths without citizens knowing who they were. But masks also meant that people could get up to no good... Eventually the wearing of masks in daily life was banned except for during certain months of the year.

However, masks continued to be used in the Commedia dell’Arte - an improvisational theatre that was popular until the 18th century. Their plays were based on established characters with a rough storyline, called Canovaccio. If you’ve read ‘The Mask of Aribella’ that name might sound familiar…

During the Black Death, plague doctor masks were also worn in Venice. These masks had long, white beaks, which were filled with sweet-smelling herbs and used to protect the wearer from breathing in infections, which at the time people believed to be airborne. I’ve used this iconic mask as the Mask Maker’s mask in ‘Aribella’.

Nowadays, masks are the fodder of superheroes such as Spiderman and Zorro who wear masks to protect their identities. Masks were used interestingly in the new ‘Watchmen’ TV series, which imagines a world where police also wear masks to protect their identities. There are several great lines, such as: "You can't heal under a mask [...] Wounds need air." and ‘Masks allow men to be cruel’.

So, in conclusion, masks can, and have, been used for many different purposes, even within a particular culture. I love the empowering, spiritual side of masks and decided to use masks in my story as a tool that could not only hide their wearers (by making them ‘unwatchable’), but also help them become more fully themselves and access the unique strengths inside of them. We all wear masks to greater or lesser extents in our lives. At the start of the novel, Aribella is hiding from the people around her. However, throughout the course of the book, she learns to trust her own power. When she eventually gets a mask of her own, one that is made for her, and puts it on, she knows she will never hide again. I think lots of young people could learn to trust themselves a little more and drop some of the false masks that we all hide behind in order to fit in. Imagine a world where we all fearlessly showed our true selves and unique powers? What a magical place that would be.

THE MASK OF ARIBELLA by Anna Hoghton is out now in paperback (£6.99, Chicken House)

In this guest blog post, author Anna Hoghton explains how she researched a key motif in her debut novel for children and shares some of her findings. A great read for anyone who has read the book, or wants to, and for teachers who want to encourage children to research information for their own stories:

In this guest blog post, author Anna Hoghton explains how she researched a key motif in her debut novel for children and shares some of her findings. A great read for anyone who has read the book, or wants to, and for teachers who want to encourage children to research information for their own stories:Masks are clearly important in the world of my book – I mean, they’re in the title and on the front cover. Given that I was writing about Venice, I always knew I would use masks, it was just a question of how. What did I want masks to mean for my characters?

For inspiration, I investigated into how masks have been used throughout history. Masks have been used for centuries and the oldest mask ever found is from 7000 BC, though the art of mask making is likely to be even older than this. There are as many different styles of masks as there are different cultures and they’ve been used for everything: rituals, ceremonies, hunting, feasts, wars, in performances, theatres, fashion, art, sports, films, as well as for medical or protective reasons. Here are a few examples of how masks have been used by everyone from the ancient Greeks to Spiderman.

Ancient Greece

The iconic smiling comedy and frowning tragedy masks were used in ancient Greek theatre. Paired together, they showed the two extremes of the human psyche. Before this, Greeks also used masks in ceremonial rites and celebrations during the worship of Dionysus at Athens.

West Africa

In West Africa, masks are still used by some tribes (such as the Edo, Yoruba and Igbo cultures) as a way of communicating with ancestral spirits. These masks are skilfully made out of wood and often have human faces, though they are sometimes in the shapes of the animals. Some tribes believe that these animal masks allow them to communicate with the animal spirits of savannas and forests. Some tribes also use war masks with big eyes, angry expressions and bright colours to scare their enemies.

North America

In North America, the skilled woodworkers in coastal Inuit tribes make complex masks from wood, leather, bones and feathers. These masks are cleverly crafted, often with movable parts, and are very beautiful. Used in shamanic rituals, these masks represent the unity between the Inuit people, their ancestors and the animals that they hunt. When people are sick, the masks are also used to exorcize the evil spirits from them.

Oceania

In Oceania, where the culture of ancestral worship is very important, masks are made to represent ancestors. Sometimes these masks are enormous, even six metres high. They are also used to ward off evil spirits.

Latin America

Latin AmericaIn Latin America, Ancient Aztecs used masks to cover the faces of their deceased. At first these funeral masks were made from leather, but later they were made out of copper and gold.

Venice (of course I had to mention this one)

In the Republic of Venice, the concealment of identity was part of daily activity and used to break down social boundaries. This was useful as it meant state inquisitors could find out truths without citizens knowing who they were. But masks also meant that people could get up to no good... Eventually the wearing of masks in daily life was banned except for during certain months of the year.

In the Republic of Venice, the concealment of identity was part of daily activity and used to break down social boundaries. This was useful as it meant state inquisitors could find out truths without citizens knowing who they were. But masks also meant that people could get up to no good... Eventually the wearing of masks in daily life was banned except for during certain months of the year.However, masks continued to be used in the Commedia dell’Arte - an improvisational theatre that was popular until the 18th century. Their plays were based on established characters with a rough storyline, called Canovaccio. If you’ve read ‘The Mask of Aribella’ that name might sound familiar…

During the Black Death, plague doctor masks were also worn in Venice. These masks had long, white beaks, which were filled with sweet-smelling herbs and used to protect the wearer from breathing in infections, which at the time people believed to be airborne. I’ve used this iconic mask as the Mask Maker’s mask in ‘Aribella’.

Nowadays, masks are the fodder of superheroes such as Spiderman and Zorro who wear masks to protect their identities. Masks were used interestingly in the new ‘Watchmen’ TV series, which imagines a world where police also wear masks to protect their identities. There are several great lines, such as: "You can't heal under a mask [...] Wounds need air." and ‘Masks allow men to be cruel’.

So, in conclusion, masks can, and have, been used for many different purposes, even within a particular culture. I love the empowering, spiritual side of masks and decided to use masks in my story as a tool that could not only hide their wearers (by making them ‘unwatchable’), but also help them become more fully themselves and access the unique strengths inside of them. We all wear masks to greater or lesser extents in our lives. At the start of the novel, Aribella is hiding from the people around her. However, throughout the course of the book, she learns to trust her own power. When she eventually gets a mask of her own, one that is made for her, and puts it on, she knows she will never hide again. I think lots of young people could learn to trust themselves a little more and drop some of the false masks that we all hide behind in order to fit in. Imagine a world where we all fearlessly showed our true selves and unique powers? What a magical place that would be.

THE MASK OF ARIBELLA by Anna Hoghton is out now in paperback (£6.99, Chicken House)

Labels:

children's books,

children's literature,

guest post

Thursday, 16 January 2020

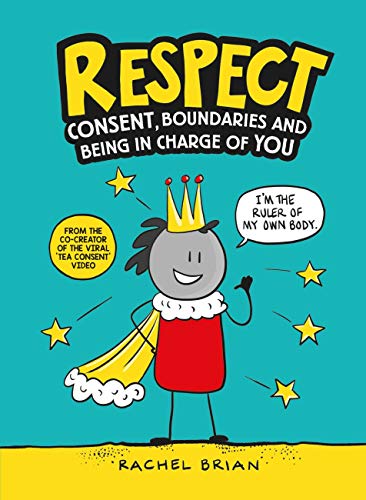

Book Review: Respect: Consent, Boundaries and Being in Charge of YOU by Rachel Brian

When a book is pounced upon and read within moments of it entering the house, it is fairly indicative of a good book. Sure, it means that someone is judging by the cover, but I believe that is why publishers, illustrators, authors and such other folk really spend time on getting the cover right.

When a book is then read by the entire household in quick succession you get another sense of its importance: it wasn't just the cover that worked but the contents too. And given that Rachel Brian (co-creator of the viral Tea Consent video and the follow-up Consent For Kids) is responsible not only for the cover but for the innards of this book, that's two marks for her.

However, there is something even more special about a book entering the house and being read by all members of the family: when you are really hoping that it is read and digested and it is. You see, Rachel Brian's new book is called 'Respect' and it is about 'consent, boundaries and being in charge of you'. When you have three children growing up in a world which has recently shed light on how terribly people can be exploited by others, it's good to know that there are child-friendly resources available to help to protect them.

In no uncertain terms, this book uses language and pictures which appeal directly to children to give a slow walk through exactly what is meant by consent. The thrust of the book is that we can make our own choices about what happens to our bodies. 'Respect' doesn't refer to sex (the closest thing it gets to this is a panel about taking and sharing pictures of people under 18 with no clothes on); instead, the focus is on more every-day scenarios where we have a choice about our own bodies.

The book also contains an all-important chapter about respecting other people's boundaries. It could be argued that this is the most crucial part of the book: it places the responsibility on us to control our own actions rather than expecting others to take preventative measures against our potential non-consensual actions. Another chapter focuses on what the reader can do if they witness abuse of someone else.

With many a humourous touch, a whole host of funky cartoons and some exceedingly sensitively-written text, this book is an essential read for... well, pretty much everyone, old and young alike. It's the sort of thing teachers and parents should be jumping at the chance to read with their children - and the children won't be complaining either. Not many books exist like this - many books about such issues can be a bit twee, or don't contain enough to appeal to the intended audience - so I welcome this little book with open arms and hope that there are more where it came from.

WREN & ROOK | £7.99 | HARDBACK | 9TH JANUARY 2020

When a book is then read by the entire household in quick succession you get another sense of its importance: it wasn't just the cover that worked but the contents too. And given that Rachel Brian (co-creator of the viral Tea Consent video and the follow-up Consent For Kids) is responsible not only for the cover but for the innards of this book, that's two marks for her.

However, there is something even more special about a book entering the house and being read by all members of the family: when you are really hoping that it is read and digested and it is. You see, Rachel Brian's new book is called 'Respect' and it is about 'consent, boundaries and being in charge of you'. When you have three children growing up in a world which has recently shed light on how terribly people can be exploited by others, it's good to know that there are child-friendly resources available to help to protect them.

In no uncertain terms, this book uses language and pictures which appeal directly to children to give a slow walk through exactly what is meant by consent. The thrust of the book is that we can make our own choices about what happens to our bodies. 'Respect' doesn't refer to sex (the closest thing it gets to this is a panel about taking and sharing pictures of people under 18 with no clothes on); instead, the focus is on more every-day scenarios where we have a choice about our own bodies.

The book also contains an all-important chapter about respecting other people's boundaries. It could be argued that this is the most crucial part of the book: it places the responsibility on us to control our own actions rather than expecting others to take preventative measures against our potential non-consensual actions. Another chapter focuses on what the reader can do if they witness abuse of someone else.

With many a humourous touch, a whole host of funky cartoons and some exceedingly sensitively-written text, this book is an essential read for... well, pretty much everyone, old and young alike. It's the sort of thing teachers and parents should be jumping at the chance to read with their children - and the children won't be complaining either. Not many books exist like this - many books about such issues can be a bit twee, or don't contain enough to appeal to the intended audience - so I welcome this little book with open arms and hope that there are more where it came from.

WREN & ROOK | £7.99 | HARDBACK | 9TH JANUARY 2020

Labels:

Book review,

book reviews,

children's books,

consent,

pshce,

pshe

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)