An excerpt from 'To Kill A Mockingbird':

"Miss Caroline started the day by reading us a story about cats. The cats had long conversations with one another, they wore cunning little clothes and lived in a warm house beneath a kitchen stove. By the time Mrs Cat called the drug-store for an order an order of chocolate malted mice the class was wriggling like a bucketful of Catawba worms. Miss Caroline seemed unaware that the ragged, denim-shirted and floursack-skirted first grade, most of whom had chopped cotton and fed hogs from the time they were able to walk, were immune to imaginative literature."

Reading this reminded me of the argument post-2016 reading SATs paper. Many thought the stories (and their vocabulary) were out of the realms of accessibility for many year 6 children. After all, most ten-year-olds have never rowed a boat to a little island, let alone ridden an albino giraffe. But, so the argument goes, neither has the most experienced and privileged of children ever gone to steal a precious stone from a dragon, along the way meeting dwarfs, elves and goblins and procuring for themselves in the process a magic ring. For many of us stories are the means by which we experience events and happenings that our everyday lives could not possibly provide.

However,

Anne Kispal's 'Effective Teaching of Inference Skills for Reading' says (on page 17) that 'the importance of background knowledge cannot be over-stressed' and summarises (on page 23) that the factors common to those who are adept at automatic inferencing are, among others, a wide background knowledge and a sharing of the same cultural background as that assumed by the text.

Lee, through the voice of Scout Finch, posits the idea that children of limited life experience are 'immune to imaginative literature'. Is this true? Does the breadth of our actual experience allow us to access further experiences in fiction? Lee makes the point that children who are so accustomed to the realities of animals find it ridiculous to relate to a story where the animals are anthropomorphised, which is probably a fair point. A story about farmers and animals behaving as animals would perhaps have been better received, but that would not have broadened the scope of the hearers.

So, we ask the question: What is the point of reading? There are obviously many possible answers to this question, but for the sake of this discussion I'll follow that question with another: Should we read only about what we know or should we read widely to expand what we know? The answer is obvious.

However, many of us would attest to knowing children who appear to be 'immune to imaginative literature'. So we must ask our selves how immunity is compromised. The answer is: by repeat attacks, often from more than one infection or from virus that has adapted to beat the immune system. What does that mean for breaching the 'immune system' of someone who does not engage with fiction? We must:

Repeatedly attack their immune system: Giving up isn't an option. Continuous exposure to stories and books will break down their immunity eventually and they will gradually find themselves able to enter into, and enjoy, fictional worlds. In general, children who grow up from a young age listening to stories want to hear more stories.

Attack with more than one infection: Provide stories of different genres (humorous, mystery, romance, classic, gothic, suspense, horror, adventure, quest, fantasy) and in different formats (picture books, short films, comics, short stories, long stories, text maps, cartoon strips, novels, fictional, factual, biographical). Eventually a wide and varied diet of infectious stories will take effect. Often children, through this exposure, will find their weakness: the books they love the most.

Attack with adapted viruses: Provide stories that are differentiated based on need. Some children need the expert advice of an adult who can pick out just what will appeal to them - perhaps the chink in their immune system's armour is a book about adventurous construction vehicles. A parent or teacher may be the only one capable of identifying that need. Once the digger-obsessed child reads that book, then he may find he has a thirst for adventure stories, at which point a whole canon of books may suddenly become more appealing to him: immune system breached.

*Leaving the analogy behind now; it is key that we prepare children for exposure to texts on subjects on which they have no knowledge and prior experience. With an immersive curriculum where vocabulary is focused on children can be prepared for the new concepts that they come across in narratives. Using non-fiction books, images, videos, drama and real-life rich experiences children can be brought into the world of the novel they are about to read or are currently reading, leading to a greater understanding of the plot and content, for example. This is a very short summary of a huge idea which will allow children to access almost any text -

I have written a separate blog post to cover these ideas.

Some sceptics may question why we put so much effort into compromising a child's immunity to imaginative literature. The reasons are many fold: stories widen our experience and understanding of the world, reading stories is enjoyable, stories encourage creativity and they provide us with a voice with which to tell our own story. One of human nature's most basic concepts is the way we see life past, present and future as a story; story-hearing and story-telling is written into our DNA. Stories are important.

Although Miss Caroline seems to have judged her class wrongly, it might just be that she had the right idea: exposing children to imaginative literature, even if the first time it falls on deaf ears, is an important part of their education. In this we can follow her example. Only, Beatrix Potter might not be the best choice for the rough-and-tumble Scout Finches of this world.

*with thanks to the staff at Penn Wood Primary for some clarification and food for thought on this issue.

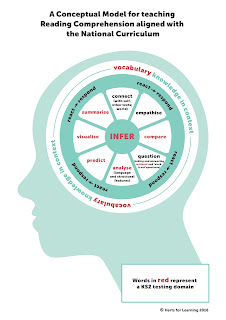

Penny Slater's helpful article 'Reading Re-envisaged' explores the links between vocabulary knowledge and inference skills. Her conceptual model (pictured left) represents how inference skills rely on good knowledge and understanding of vocabulary. In her own words:

Penny Slater's helpful article 'Reading Re-envisaged' explores the links between vocabulary knowledge and inference skills. Her conceptual model (pictured left) represents how inference skills rely on good knowledge and understanding of vocabulary. In her own words: