Timetabling - my reading lessons happen on Wednesday, Thursday and Friday from 8:45 - 9:45. The children come in to a 'Do Now' which usually involves reading the day's chapter/passage/excerpt independently (more on this later). On those mornings I also teach writing-focused English for the following hour and then 1.5 hours of maths after break.

Whole-Class Reading - I do not have a 'traditional' carousel of activities. All children read and answer questions about the same text; research shows that children benefit from being exposed to higher level texts (when the teacher reads it aloud to them before they answer questions on it). Many of my reading lessons are based on a class novel which we read over a half term or a term; to facilitate this we have 'class sets' of many quality texts. Many people ask how the lower prior attainers can be catered for in these sessions - I've written more about that here. For more on the ideology behind whole-class reading please read Rhoda Wilson's blog post about it.

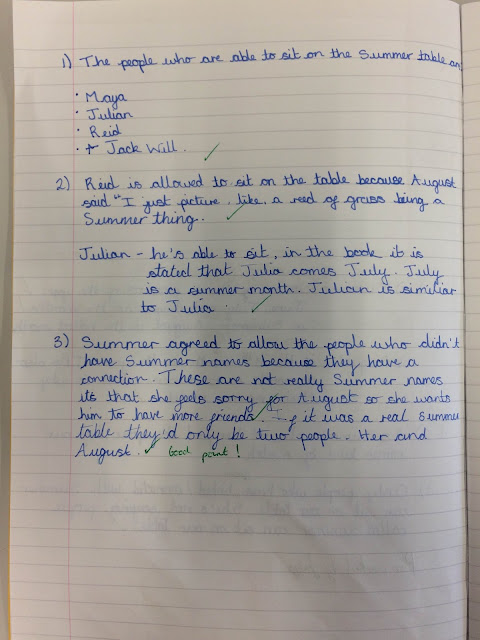

Lesson Sequence - During these sessions I ask the children to first read the chapter/excerpt independently, then I read the same passage aloud, then without discussion the children attempt to independently work through the questions giving written answers. Once the majority of children have done this we hold a whole-class discussion and I (or children who have written good answers) model best answers and children edit what they have written (in purple so as to distinguish their original answer from their edited answer). This sequence was inspired by Reading Reconsidered by Doug Lemov. This will usually be followed by a period of reading aloud the next part of the text (usually by me but I plan to begin to ask children to read aloud more often) which is often, but not always, accompanied by lots of discussion and modelling of my thought processes as a reader.

Reading For Pleasure - Many school plan elaborate initiatives in an attempt to entice children into reading with the hope that this will lead to them choosing to read for pleasure. My reading lessons always contain a time of just reading the class novel for enjoyment - books are the most powerful tool when it comes to getting children to love and enjoy reading. I've written more about it here in my blog post entitled 'On Why I'll Still Be Dressing Up For World Book Day And The Power Of Books'.

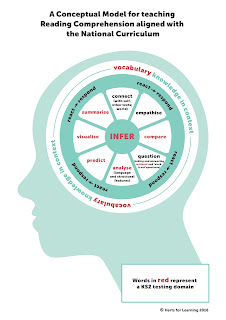

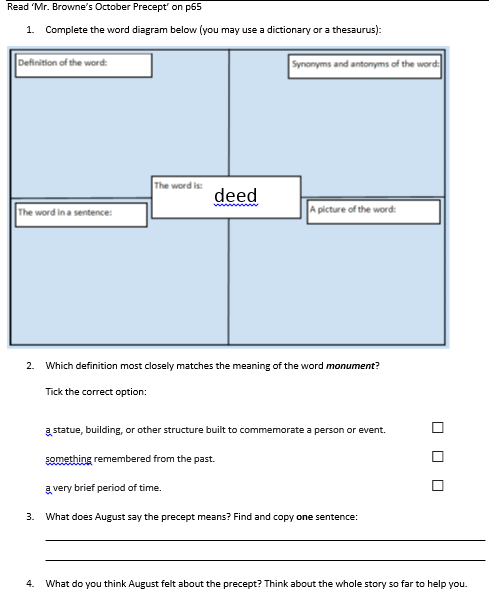

Comprehension Activities - I use the various question stem documents which are available to set my questions, and I colour-code each question and put the relevant Reading Roles symbol with them (see below for more on Reading Roles). Many of these comprehension activities will follow my Scaffolding Inference structure (see below) although I do teach other lessons which focus on the other cognitive domains. Examples of these activities can be found here. I have written a whole blog post entitled 'How To Write Good Comprehension Questions' which gives more insight into how I go about setting questions for reading lessons. In at least some lessons there is a focus on particular reading strategies, such as inference-making which I have written about here: Questions To Ask When Teaching Inference-Making.

Reading Roles - help children and staff understand the 8 cognitive domains. Each of the cognitive domains is colour-coded and has a symbol assigned - as mentioned, we use these colours and symbols when designing our comprehension activities. Reading Roles have been used by other teachers in other schools - some of them have written about it here.

Scaffolding Inference - this is something I've designed and developed based on research and findings from last year's SATs. Please see the quick reference guide which outlines this approach. I would say that this is the most effective thing I have done as it focuses on the reading test's three key areas: vocabulary, retrieval and inference. Not only can inference be scaffolded, other reading strategies can too: Scaffolding Structures For Reading Comprehension Skills.

Growing Background Knowledge - this isn't always easy to do as background knowledge can vary so much from child to child. What we do know is that our understanding of a text hinges greatly on what we already know - this might be a knowledge of vocabulary or just a more general knowledge. I have written about possible strategies to take when it comes to building children's background knowledge: 5 Ways To Make Texts With Unfamiliar Contexts More Accessible To Children; Attacking Children's Immunity To Imaginative Literature.

EAL reading activity structure - this is an activity (again, linked to the Reading Roles) which I have designed based on research on how to support EAL learners when accessing new texts.

Pairing non-fiction texts with fiction texts - this increases understanding of both the fiction text and the non-fiction text and has sparked some really deep conversations about moral, ethical and religious issues. I have also written about this for the TES: Why Every Primary School Needs To Embrace Non-Fiction.

We also use these resources in English lessons (with our Talk 4 Writing texts) and topic lessons - much of our work centres around texts so these activities help to ensure children comprehend the information.

The fruit of this approach is that in December over 50% of children in my group taking the 2016 KS2 Reading Test were working at or above average (according to the test's thresholds) after one term of year 6. This is a dramatic increase when compared to my results in last year's END of year results based on the same test.

If there is something you feel I've not covered, please ask and I will edit this to give a fuller picture of my approach. I'm not assuming it to be a silver bullet but am seeing good results after teaching in this way for a term.

If you would like Aidan to work with you on developing reading at your school, please visit his website at https://www.aidansevers.com/services and get in touch via the contact details that can be found there.

Click here to read about how following these approaches impacted on our SATs results.

Further reading about reading from my blog:

Being A Reading Teacher

Reading: 2 Things All Parents and Teachers Must Do

Reading: Attacking Children's Immunity To Imaginative Literature

Reading for Pleasure

Changing Hearts, Minds, Lives and the Future: Reading With Children For Empathy

The Best RE Lesson I Ever Taught (Spoiler: It Was A Reading Lesson)

The Unexplainable Joy of Comparing Books

The More-ness of Reading

The Power Of Books

Click here to read about how following these approaches impacted on our SATs results.

Further reading about reading from my blog:

Being A Reading Teacher

Reading: 2 Things All Parents and Teachers Must Do

Reading: Attacking Children's Immunity To Imaginative Literature

Reading for Pleasure

Changing Hearts, Minds, Lives and the Future: Reading With Children For Empathy

The Best RE Lesson I Ever Taught (Spoiler: It Was A Reading Lesson)

The Unexplainable Joy of Comparing Books

The More-ness of Reading

The Power Of Books